En 2009, un membre du Politburo chinois a décidé de découvrir ce qu'Internet avait recueilli à son sujet. Il a recherché son propre nom sur Google et, eh bien, il est devenu extrêmement en colère en parcourant les résultats. La vengeance était la seule réponse.

Peu de temps après, un groupe chinois de menaces persistantes avancées (APT) connu sous le nom d’Elderwood Group a compromis le réseau d’entreprise de Google. Le groupe a dérobé une part importante de propriété intellectuelle et a tenté d’accéder aux comptes de messagerie de militants des droits de l’homme. Les services de sécurité de l’État ont enquêté sur le compte bancaire de l’une des cibles. En conséquence, Google a modifié sa position concernant google.cn-it : il cessera de censurer les résultats de recherche ; si un moteur de recherche non censuré est reconnu coupable d’infraction à la loi, il devra quitter définitivement le pays. Des visiteurs du siège de Google à Pékin ont déposé des fleurs sur le panneau, qui ont été qualifiées d’« hommage floral illégal » et retirées avec agacement.

Il convient de noter que Google n'a pas été la seule victime. Dans une initiative baptisée Opération Aurora, les attaquants ont ciblé au moins 20 autres grandes entreprises en exploitant des vulnérabilités dans Internet Explorer (soupir) et un système de contrôle de versions appelé Perforce. L'objectif principal était d'accéder aux dépôts de code source de diverses entreprises de technologie et de défense et de les modifier. De manière surprenante, personne n'avait jamais pensé à sécuriser ces conteneurs grands ouverts de précieuse propriété intellectuelle ! Les systèmes compromis ont établi des connexions TLS sortantes vers des serveurs de commande et de contrôle (C&C) situés en Illinois, au Texas et à Taïwan en utilisant des machines virtuelles volées appartenant à des clients de Rackspace. Ils ont exploré des réseaux connectés pour trouver des dépôts et d’autres systèmes vulnérables.

De 2014 à 2018, Google a entièrement repensé son architecture d’accès afin de prévenir de telles attaques à l’avenir. L’ensemble des utilisateurs, même ceux travaillant dans les bureaux de Google, ont été déplacés vers un réseau sans privilèges. Ils se trouvent, de fait, « en dehors » du réseau d’entreprise et ne bénéficient que d’une connexion Internet. Tout accès, qu’il provienne de ce réseau ou d’un autre, transite par un proxy d’accès qui s’adapte en fonction de l’identité. Aucun autre réseau classique n’est en place. Google a conclu que les réseaux d’entreprise ne sont pas moins dangereux que l’Internet public et que prétendre le contraire est malhonnête.

Officiellement documenté et implémenté sous BeyondCorp, l’accès dépend uniquement des identifiants des utilisateurs et de l’état des appareils (BeyondCorp n’autorise que les appareils gérés et nécessite une authentification 802.1X et par PKI). Il harmonise la manière dont les utilisateurs se connectent aux applications et aux données, quel que soit leur emplacement et les réseaux qu’ils utilisent, sans autre distinction entre l’accès local et l’accès distant.

ZTNA fait son apparition

Un an plus tard, en 2019, lorsque Gartner a publié son premier « Guide du marché pour l'accès réseau Zero Trust » (j'en étais l'auteur principal en tant qu'analyste Gartner à l'époque), il a identifié deux styles :

- L’approche Endpoint-initiated reprenait une spécification plus ancienne pour les périmètres définis par logiciel et était conçue pour un accès local uniquement ; elle renvoyait une liste d’applications autorisées après l’authentification de l’utilisateur.

- L’approche ZTNA service-initiated s’inspirait en partie de la conception de BeyondCorp, selon laquelle les utilisateurs et les appareils étaient considérés comme distants, même s’ils se trouvaient dans le même bâtiment. Elle a abandonné les exigences relatives aux appareils gérés, à la norme 802.1X et à l’infrastructure à clés publiques (PKI) et introduit un élément nouveau : les connexions « dedans et dehors » (inside-out).

Plusieurs startups basées sur le cloud ont adopté le modèle initié par le service car il se prêtait mieux à l’accès à distance. Un connecteur lance une session sortante vers le courtier dans le cloud du fournisseur, d’où le principe « inside-out ». Le courtier protège les applications des découvertes sur Internet et limite les mouvements latéraux.

Cependant, les fournisseurs n’ont envisagé que des scénarios d’accès à distance. Il semble que la leçon BeyondCorp ait été oubliée.

ZTNA devient universel

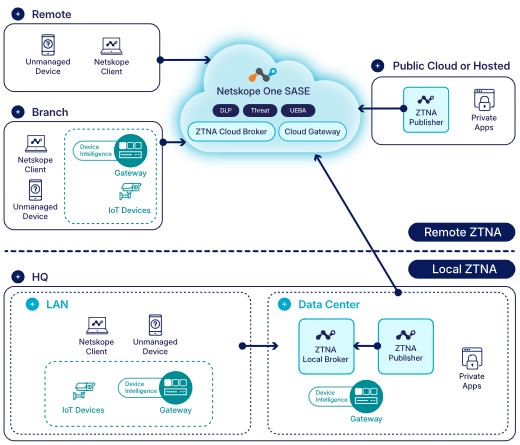

Récemment, certains fournisseurs, dont Netskope, ont ajouté des courtiers locaux sur site à leurs services ZTNA. Cette approche, baptisée « ZTNA universel », se rapproche de la philosophie de BeyondCorp. On constate d’ailleurs que Google a conçu une architecture d’accès très similaire à ZTNA, avant même que ce concept n’existe.

Examinons le ZTNA en utilisant la terminologie de Netskope. Dans votre datacenter ou votre cloud IaaS, un éditeur configuré établit une session sortante de longue durée vers la partie passerelle de l’éditeur du courtier d’accès privé dans notre cloud. Lorsqu’un utilisateur distant souhaite accéder à une ressource publiée, il se connecte comme à l’accoutumée, ce qui commence en réalité par une session vers la partie passerelle client du courtier d’accès privé. Nous relions ces sessions et l’activité se déploie. Nous appelons désormais cela ZTNA à distance, car les personnes sont éloignées de l’application.

Pour l’accès local, le ZTNA local place un courtier dans le même réseau que les ressources avec lesquelles les utilisateurs souhaitent interagir. Dans la plupart des cas, ces utilisateurs se trouvent dans le même emplacement physique qu’un datacenter. Les éditeurs établissent des sessions avec le courtier local, et lorsqu’un utilisateur se connecte à une ressource, le trafic passe par le courtier local, et non par celui situé dans notre cloud.

Pourquoi un courtier local ? Rappelons le problème du hairpinning : obliger les télétravailleurs à passer par un centre de données sur site pour accéder aux ressources Internet engendre une perte de performance. De même, le reverse-hairpinning est un problème : forcer les utilisateurs locaux à passer par un courtier basé dans le cloud pour accéder aux ressources locales entraîne également une dégradation des performances. Le trafic local doit rester local.

Le ZTNA universel combine le ZTNA distant et le ZTNA local et représente le meilleur de BeyondCorp. Il :

- Harmonise l’expérience d’accès afin que les utilisateurs n’aient pas à se demander quelle est la bonne façon d’accéder aux applications. Notre objectif est toujours de les aider à trouver le juste équilibre entre sécurité et productivité. Si nous leur imposons d’utiliser plusieurs méthodes d’accès à distance différentes de l’accès local, ils risquent d’augmenter les risques en créant des solutions de contournement non sécurisées. Nous devons faire en sorte que nos collaborateurs n’aient pas à bricoler l’infrastructure pour accomplir leurs tâches. Le ZTNA universel élimine tous les obstacles liés à l’accès et fournit une méthode unique, cohérente et sécurisée qui fonctionne quel que soit l’emplacement des utilisateurs ou des applications.

- Élimine les réseaux privilégiés qui ne sont en réalité pas plus sûrs que l’Internet. Les méthodes d’accès traditionnelles aux réseaux privilégiés continuent de présenter des risques pour ces réseaux, que ce soit via des hôtes compromis (ransomware) ou par des individus compromis (élévation de privilèges). Je dirais que le ZTNA universel supprime l’obligation de maintenir des réseaux privilégiés car le routage basé sur les adresses IP disparaît. (U)ZTNA connecte les personnes aux données, et non les appareils aux réseaux. [Remarque : dans cet article de blog, j’écris « (U)ZTNA » pour indiquer qu’une observation associée s’applique à la fois au ZTNA « normal » et au ZTNA universel.] Avant que le côté utilisateur de la connexion inside-out ne soit connecté au côté éditeur, la personne doit s’authentifier auprès de l’annuaire d’entreprise de la société. Ce paradigme s’authentifier-puis-se connecter est l’alternative sûre à la norme se connecter-puis-s’authentifier qui a été brisée depuis sa création dans les années 1970, dans laquelle rien ne peut empêcher des adversaires déterminés de lancer toutes sortes de trafic malveillant sur des sockets d’écoute innocents derrière des trous dans les pare-feux.

- Supprime les VPN traditionnels, un point d’entrée persistant et très vulnérable. Les VPN sont une technologie des années 1990 conçue à l’origine pour de petits groupes de personnes qui géraient à distance des routeurs. Ils ne peuvent tout simplement pas s’adapter aux exigences des grandes équipes hybrides aux rôles diversifiés, utilisant différents appareils dans divers états. Le (U)ZTNA fournit un accès de précision, un accès qui peut s’adapter aux rôles, aux appareils et aux états. Notez également que le (U)ZTNA élimine le pire type de serveur privilégié : un concentrateur VPN, qui tente (de plus en plus infructueusement) de faire le pont entre Internet et un réseau privilégié en s’appuyant sur un socket d’écoute innocent exposé aux aléas d’Internet non sécurisé.

- Réduit le besoin de NAC, car il se concentre sur l’accès au niveau de l’application plutôt que sur l’accès au niveau du réseau. Il n’y a plus de routage basé sur le protocole IP entre les appareils des utilisateurs et leurs destinations, et il n’y a plus de chemins vers les ports de commutation ou d’autres aspects de l’infrastructure réseau. Le simple fait d’être dans un réseau ne confère plus d’avantage si vous ne pouvez pas interagir de manière aléatoire avec ce qui s’y trouve. De plus, de nombreux projets NAC échouent parce que le matériel devient obsolète, que les temps d’arrêt ne peuvent être tolérés, que les politiques se multiplient et que les nombreux composants mobiles ne sont pas toujours bien intégrés. Le NAC présente encore un modèle de confiance implicite (accès libre au réseau après connexion), ce qui est à l’opposé des projets de sécurité modernes courants orientés vers des stratégies Zero Trust.

- Offre un accès optimisé basé sur la localisation, sans hairpins lents ou autres obstacles qui pourraient forcer les utilisateurs à trouver des solutions de contournement peu sûres. Un accès harmonisé empêche les personnes de travailler dans des conditions de sécurité médiocres. L’accès optimisé évite les compromis entre sécurité et performances. Lorsque les gens peuvent accéder immédiatement à ce dont ils ont besoin sans avoir à bidouiller le système, à se débrouiller avec des solutions de contournement ni même à réfléchir à ce qu’il faut faire en fonction de l’endroit où ils se trouvent, ils restent productifs et de bonne humeur (et les lignes téléphoniques du service d’assistance restent disponibles).

Par essence, le ZTNA universel supprime toutes les distinctions entre local et distant. L’accès est immédiat, adapté, cohérent, rapide et sécurisé. Repensez votre architecture d’accès dès maintenant avec le ZTNA universel de Netskope. Merci de votre lecture.

Mark Fabbi (un autre ex-analyste de Gartner et maintenant conseiller CXO de Netskope) et moi avons enregistré un webinaire dans lequel nous explorons davantage les avantages du ZTNA universel. Regardez maintenant.

Retour

Retour

Lire le blog

Lire le blog