概要

The Play ransomware, also known as PlayCrypt, is a ransomware that first emerged in June 2022. The ransomware has been targeting industries such as healthcare and telecommunication as well as a wide range of regions such as Latin America, Europe, and North America. The Play ransomware is known for gaining access to networks through compromised valid accounts or by exploiting specific vulnerabilities. Once inside the network, it uses a big pool of known post-exploitation tools to continue its attack. Tools like Bloodhound, PsExec, Mimikatz, and AdFind are some examples of tools previously used in attacks involving this ransomware.

Another aspect of the malware that makes it famous is the amount of anti-analysis techniques it uses in its payloads such as abusing SEH and using ROP to redirect the execution flow. By employing techniques to slow down the reverse engineering process, threat actors make detection and prevention of the malware more difficult.

Back in 2022, other researchers published an excellent blog post analyzing the malware itself and some of the anti-analysis techniques it used. In this blog post, we’ll revisit the anti-analysis techniques employed by recent variants of Play ransomware, explaining how they work and also how we can defeat some of them using automation scripts.

Return-oriented programming (ROP)

When reverse engineering malware, making sure that the control flow is not obfuscated is one of the first things we need to do in order to properly understand the malware.

As an attempt to obfuscate its control flow, the Play ransomware often uses an ROP technique in its payload. It does so by calling over a hundred functions that patch the value on the top of the stack and then redirects the execution flow to it. Before we talk about how the malware does this exactly, let’s take a look at how the CALL and RET assembly instructions work in general.

When a CALL happens (a near call in this case to be more specific), the processor pushes the value of the instruction pointer register (EIP in this case) on the stack and then branches to the address specified by the call target operand, which in this case is an offset relative to the instruction pointer. The address in the instruction pointer, plus this offset, will result in the address of the function to be called.

The RET instruction on the other hand indicates the end of a function call. This instruction is responsible for transferring the program control flow to the address on the top of the stack. And yes, this is exactly the address initially pushed by the call instruction!

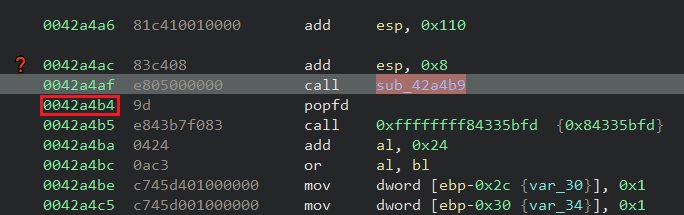

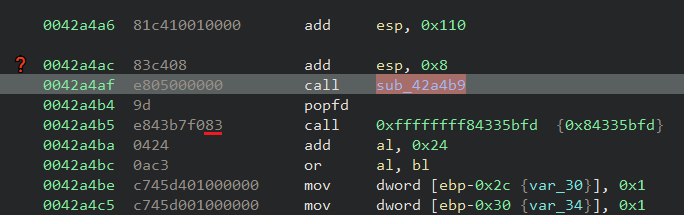

Considering what was mentioned, in an ideal scenario the highlighted address in the image below would be the next instruction to be executed after a call to the target function (sub_42a4b9):

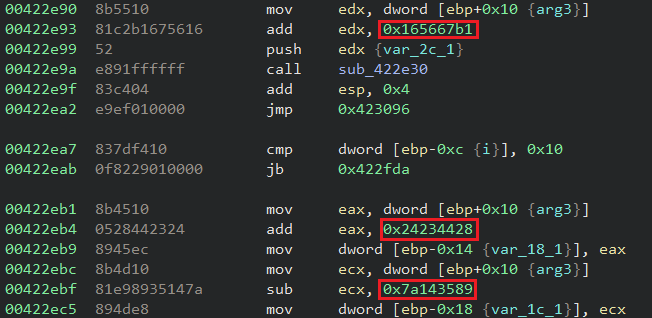

What the malware does to abuse how the CALL and RET instructions work can be observed in the following image:

Once the function is called, the address 0x42a4b4 is pushed to the stack, so ESP will point to it. The called function then adds the value 0xA to the address pointed by ESP and then returns using the RET instruction. These operations result in the control flow being redirected to 0x42a4be (0x42a4b4 + 0xa) instead of 0x42a4b4.

By applying this technique the malware makes not only static analysis more complex, since the program flow will not be trivial, but it can also make debugging harder because if you step over this type of function a lot of things can happen before the regular “next instruction” is executed.

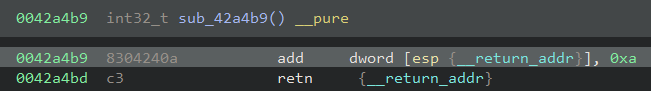

Another way the malware implements this ROP technique is by using the approach shown in the code below, which is very common in shellcodes. The offset specified by the target operand of the call instruction is zero, resulting in the address of the function to be called exactly the address of the next instruction. This address is then pushed onto the top of the stack and the rest of the operations are exactly the same as the previous example:

In order to help in the analysis of the Play ransomware, Netskope Threat Labs developed a script, based on previous work of other researchers, to fix the ROP obfuscation employed.

The script searches for possible ROP candidates, collects the offset to be added to the top of the stack and patches the addresses performing the ROP calls with an absolute jump, where the target is the modified transfer address calculated at runtime.

The following is an example of how the malware payload would look before and after the script execution:

Before:

After:

Anti-disassembling

An anti-disassembly technique used to trick analysts and disassemblers is to transfer the execution flow to targets located in the middle of other valid instructions.

Let’s take the function call at 0x42a4af used in the ROP section above as an example. The opcodes for that CALL instruction are “E8 05 00 00 00”. The byte 0xE8 is the opcode of the CALL instruction itself and the other 4 bytes represent the target operand (the offset relative to EIP).

As we discussed previously, the address of the function to be called would be the value of EIP (0x42a4b4) + the offset (0x5) and that results in the address 0x42a4b9. However, this value falls into the last byte of another valid instruction at 0x42a4b5:

In terms of execution, this type of behavior changes nothing because the processor will understand the instructions correctly. However, a disassembler might not present the instructions correctly depending on the approach it uses (e.g. linear sweep), making static analysis a bit tricky.

The script we provided to fix the ROP calls also handles this scenario for the ROP targets. Considering we use a JMP instruction to patch the calls we end up also forcing the disassembler to understand the correct flow to follow.

Junk code

Although this is a very simple technique it’s still worth mentioning because it can definitely slow down the analysis of the malware. The junk/garbage code insertion technique is exactly what the name suggests: the insertion of unnecessary instructions in the binary.

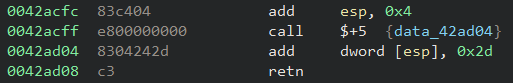

Unlike the techniques presented so far, junk code insertion would not trick the disassembler, but it might make one waste time analyzing unnecessary code and the Play ransomware uses it quite often, especially in the ROP calls targets.

Structured Exception Handling (SEH)

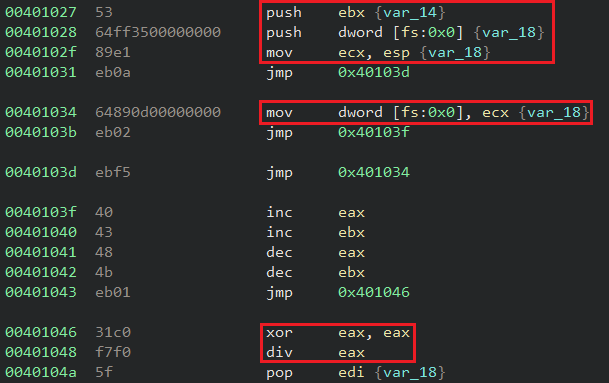

Another anti-analysis technique used by the malware is abusing a Windows mechanism called Structured Exception Handling that is used to handle exceptions.

In the Windows operating system every thread has a structure named Thread Environment Block (TEB). In an x86 environment the address of TEB is located at the FS register and it contains information useful for the thread itself and resides in the process address space. The first field of this structure is another structure called Thread Information Block (TIB) and the first item of this structure contains a list of what is called “exception registration records”.

Each of these records is composed of a structure that holds two values. The first one is a pointer to the “next” record on the list and the second one is a pointer to the handler responsible for handling the exception.

In simple terms, when an exception occurs, the last record added into the list is called and decides if it will handle the triggered exception or not. If that’s not the case the next handler in the list is called and so on until the end of the list is reached. In that case, the default Windows handler is called.

The way Play abuses this feature is by inserting its own exception handler into the exception handling list and then forcing an exception. In the example below, the EBX register contains the address of the malware exception handler and once it’s inserted as the first element of the list (the four highlighted instructions on the top) the malware then zeroes EAX and divides it by zero, causing an exception (the two highlighted instructions on the bottom):

Once the exception is triggered the last registered handler is called. The malware uses this first handler to register and call a second one by forcing a second exception, but now via the INT1 instruction to generate a debug exception. The second registered handler is the one responsible for moving forward in the “normal” malware execution.

This technique can be very annoying when debugging the malware since the debugger would stop the execution when the exception occurs, forcing us to find the exception handler and making sure we have control over it beforehand.

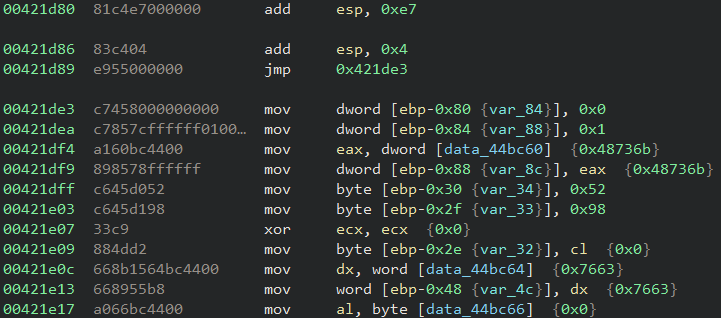

String obfuscation

All the relevant strings used by the malware are obfuscated, making it difficult to flag any relevant string statically. In order to deobfuscate its strings at runtime, the malware generates an 8-byte key and uses it as an input for the deobfuscation algorithm.

The algorithm to generate the key is quite simple. It receives a hardcoded seed value and performs some basic arithmetic operations within a loop. The loop counter is also a hardcoded value that used to be very large in the analyzed samples (e.g. 0x20c87548).

We can simplify the operations used to generate the key in the following python snippet:

x = seed

y = 0

i = 0

while i < counter:

a = (x * x) >> 32

b = (x * y) + (x * y)

if y:

y = (a + b) & 0xffffffff

else:

y = a

x = ((x * x) & 0xffffffff) + i

i += 1

key = struct.pack("<2I", *[x, y])

The algorithm used to deobfuscate the strings involves a few more steps and some other operations such as AND, OR, and NOT. These operations are applied in the obfuscated string itself and the last step of the deobfuscation loop is to apply a multi-byte XOR operation using the previously generated 8-byte key. The operations can be simplified in the following python snippet:

i = 0

while i < len(enc_str):

dec_str[i] = enc_str[i]

j = 0

while j < 8:

v1 = (dec_str[i] >> j) & 1

v2 = (dec_str[i] >> (j + 1)) & 1

if v1 != v2:

if v1 == 0:

dec_str[i] = (dec_str[i] & ~(1 << (j + 1))) & 0xFF

else:

dec_str[i] = (dec_str[i] | (1 << (j + 1))) & 0xFF

if v2 == 0:

dec_str[i] = (dec_str[i] & ~(1 << j)) & 0xFF

else:

dec_str[i] = (dec_str[i] | (1 << j)) & 0xFF

j += 2

dec_str[i] = ~dec_str[i] & 0xFF

dec_str[i] = (dec_str[i] ^ key[i % len(key)]) & 0xFF

i += 1

It’s worth mentioning that the algorithms contain a lot of junk operations that are not necessary for the deobfuscation itself and those were removed in the presented snippets.

The Netskope Threat Labs team created two scripts to help in the deobfuscation process: one to generate the 8-byte key automatically, and another one to perform the string decryption.

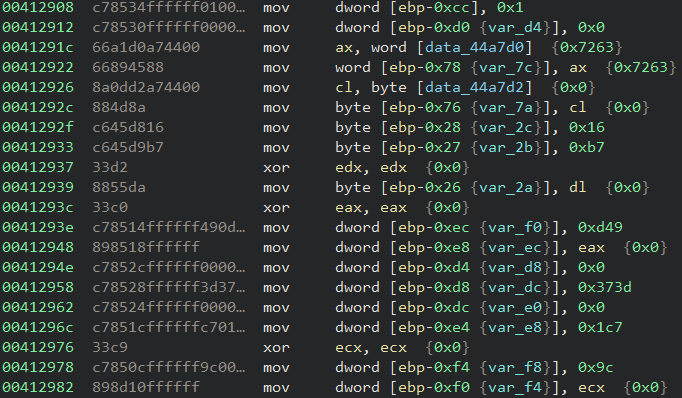

API hashing

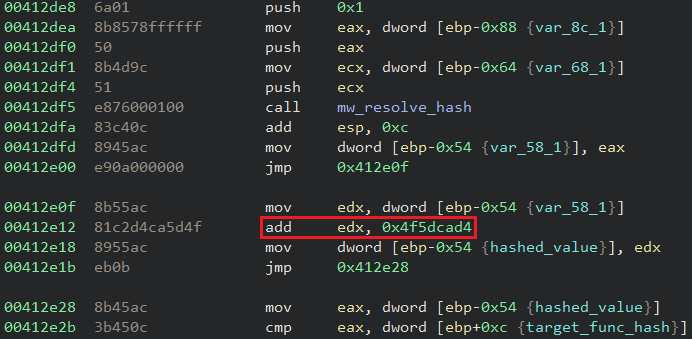

The malware uses the well-known API Hashing technique to resolve the Windows API functions it uses at runtime. The algorithm used is the same as the one flagged in 2022 which is xxHash32, with the same seed of 1 provided to the hashing function.

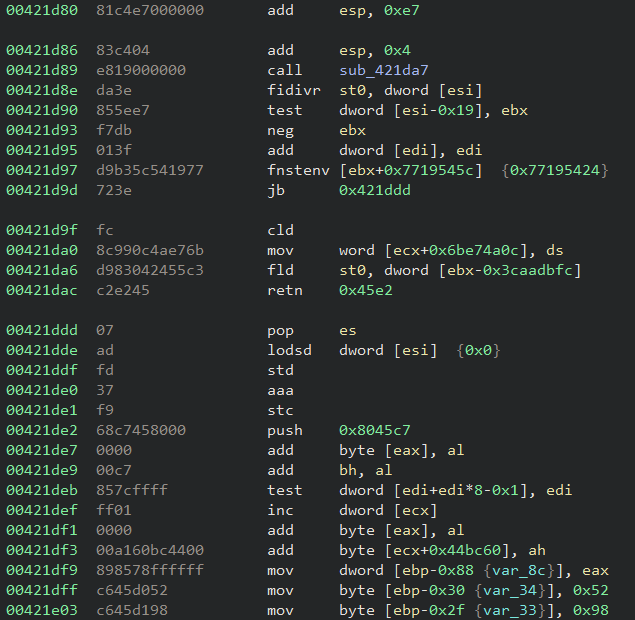

The xxHash32 algorithm can be easily recognized due to the amount of constants it uses in its operations:

As an attempt to obfuscate the hashed functions even more, the malware adds or subtracts specific constants to the hash results. The constant value is different for each sample. The following is an example where the malware added the value 0x4f5dcad4 to the hash result:

Netskope detection

- Netskopeの脅威対策

- Win32.Ransomware.Playde

- Netskope Advanced Threat Protection provides proactive coverage against this threat.

- Gen.Malware.Detect.By.StHeur and Gen:Heur.Mint.Zard.55 indicates a sample that was detected using static analysis

- Gen.Detect.By.NSCloudSandbox.tr indicates a sample that was detected by our cloud sandbox

結論

As we can observe in this blog post, the Play ransomware employs multiple anti-analysis techniques as an attempt to slow down its analysis. From string obfuscation to ROP and the usage of SEH hijacking, threat actors are often updating their arsenal and expanding their techniques to make the impact of their attacks even more destructive. Netskope Threat Labs will continue to track how the Play ransomware evolves and its TTP.

IOCs

All the IOCs related to this campaign, scripts, and the Yara rules can be found in our GitHub repository.

Back

Back

ブログを読む

ブログを読む