Summary

A month ago, Google released eight new top level domains (TLD). Two of them (.zip and .mov) have been a cause for concern because they are similar to well known file extensions. Both .zip and .mov TLD are not new, as they have been available since 2014. The main concern is that anyone now can own a .zip or .mov domain and be abused for social engineering at a cheap price.

Because both of these TLDs are indistinguishable from the file extensions, they can be a great bait for threat actors. In this blog post, we will provide some samples of how threat actors can take advantage of .zip and .mov domains, and provide the current state of these domains just a month after their release.

The risks of .zip and .mov domains

ZIP and MOV are ubiquitous file extensions with which most users will be familiar. ZIP files are compressed archives used to store one or more files and are natively supported by every major OS. MOV is a popular video format that is widely used on Apple platforms and is the default format of videos in iOS devices.

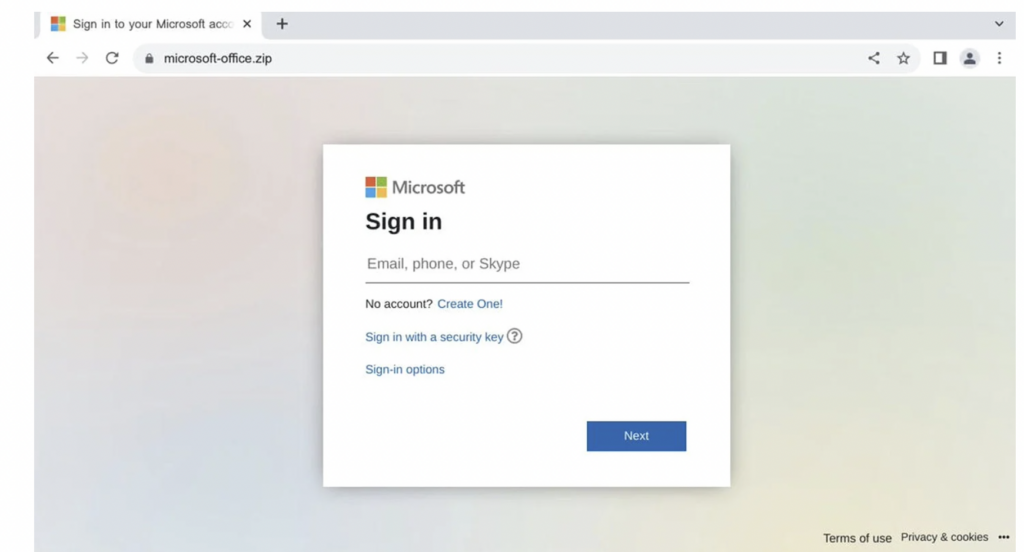

The risk with the .zip and .mov domains is that attackers will be able to craft URLs that appear to be delivering ZIP and MOV files, but instead will redirect victims to malicious websites. Crafting URLs that look benign to the victims, but are actually malicious, is a common social engineering technique used by attackers. Some examples of domain spoofing techniques include IDN homograph or typosquatting where attackers register domains with typographical similarities to legitimate ones.

URL Scheme Abuse

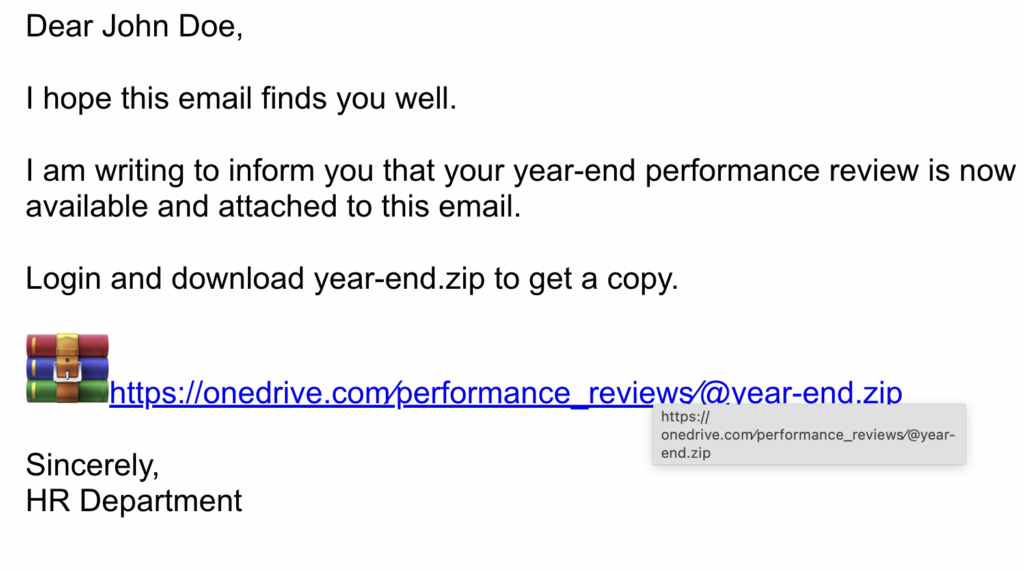

One way attackers can take advantage of the .zip domain is through the URL scheme abuse. The sample malicious email below purports to be HR from a company that sends a “year-end performance review”. Users who have gone through phishing awareness drills might check if the domain of the URL is legitimate and might sometimes hover over the URL to see if it resolves to the same link. However when the user clicks on the link, they would actually go to the domain “year-end.zip” because anything before the “@” sign is considered user info and that is stripped off by some browsers.

From this example, threat actors may host a malicious file from the “year-end.zip” domain, or just phish for the target’s login information.

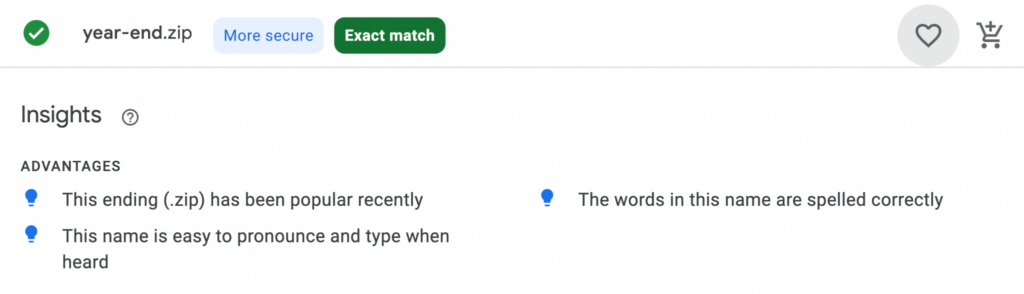

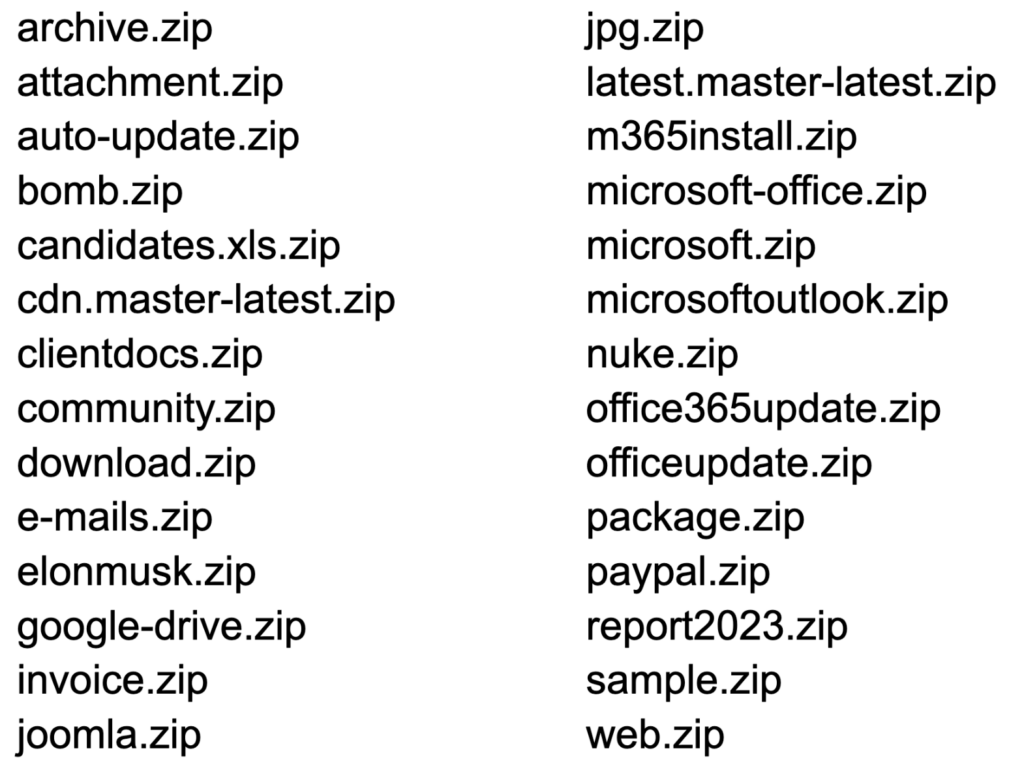

And since .zip domains are now available to the public, attackers can register domains that look like compressed files to use them in attacks, like the one we demonstrated above.

Here are some domains that were created to look like .zip files that Netskope Threat Labs has found as we monitor for abuse.

Event Driven Phishing

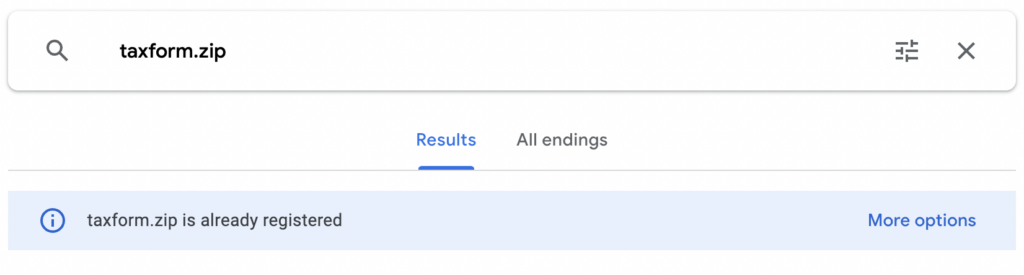

Another way threat actors can abuse the .zip domain is through event driven phishing. Scammers are known to use significant events as social engineering bait. For example, during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a lot of COVID-themed phishing. Similarly, tax-themed phishing usually comes along just in time for filing income tax returns. We can expect future significant events will be used as a theme for phishing emails. Combining this strategy with a .zip TLD can be a great tool for attackers, especially for event themes where users expect to receive file attachments.

Tracking .zip and .mov Abuse

Just one month into Google making .zip domains publicly available, we are already seeing them being used to deliver malicious payloads.

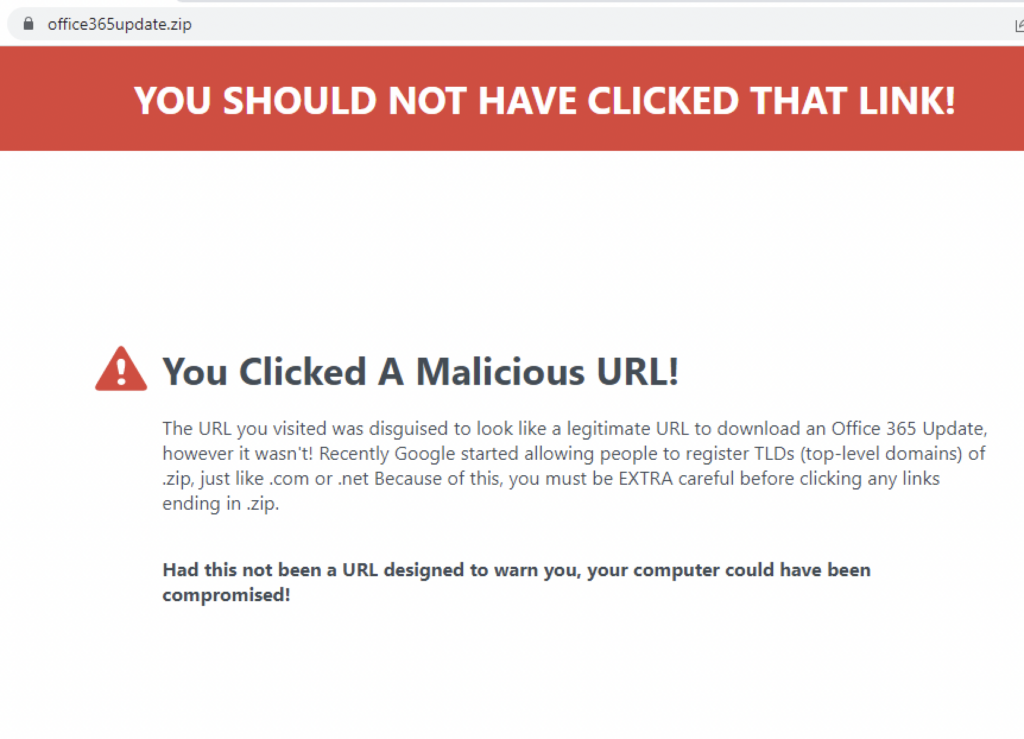

So far, Netskope Threat Labs found that 18% of .zip and .mov domains Netskope users are visiting are used to distribute malicious content. While the other 82% are currently benign, the majority of those are not hosting actual content yet. Other .zip domain owners have used the domains to try to educate others against the risks of URL scheme abuse and the .zip TLD.

While the number of domains being abused to deliver malicious payloads is currently low, users should still be cautious as we expect this to increase in the future.

Some of the benign .zip and .mov domains Netskope Threat Labs are tracking are being sold or have no actual content yet which can be abused later on. It is also known that some threat actors let their domains age to avoid detection.

Conclusion

Threat actors will use and abuse anything that can give them leverage to achieve their malicious purposes. With the availability of .zip and .mov domains to the public, it is expected that they will ramp up the use of these domains for social engineering. However, like any other types of social engineering attack, being mindful and vigilant against URLs on email or any other social communication applications is still vital to prevent falling into these traps. Scanning network traffic should also suffice for social engineering abuse of .zip and .mov domains.

Recommendations

Though currently it is not widely used for social engineering, there do not appear to be any significant, legitimate services using the .mov or .zip TLDs. Therefore, blocking the .mov and .zip TLDs is currently a useful strategy for reducing exposure. However, this advice may change moving forward if some popular services start using the .mov and .zip TLDs. Otherwise, using a product like the Netskope NG SWG will block known malicious domains and inspect HTTP and HTTPS traffic to block any malicious content. Users should always access important pages, like their banking portal or webmail, by typing the URL directly into the web browser instead of using search engines or any other links, as the results could be manipulated by SEO techniques or malicious ads.

Netskope Threat Labs recommends that organizations review their security policies to ensure that they are adequately protected against these and similar phishing pages and scams. Other recommendations include:

- Inspect all HTTP and HTTPS traffic, including all web and cloud traffic, to prevent users from visiting malicious websites. Netskope customers can configure their Netskope NG-SWG with a URL filtering policy to block known phishing and scam sites, and a threat protection policy to inspect all web content to identify unknown phishing and scam sites using a combination of signatures, threat intelligence, and machine learning.

- Use Remote Browser Isolation (RBI) technology to provide additional protection when there is a need to visit websites that fall into categories that can present higher risk, like newly observed and newly registered domains.

- Block .zip and .mov TLDs if they do not serve any legitimate business purpose.

IOCs

Below are the IOCs related to the web pages analyzed in this blog post.

Domains:

newdocument[.]zip

businesscentral[.]zip

e-mails[.]zip

42[.]zip

microsoft-office[.]zip

bobm[.]zip

Back

Back

ブログを読む

ブログを読む