Co-authored by Jeff Brainard and Jason Hofmann

In more than one conversation with large enterprise clients, we’ve heard the networking and infrastructure leaders responsible for managing the organization’s global WAN jokingly refer to themselves as the “Chief Hairpinning Officer” or CHO. At first blush, this provides a laugh. But there’s more than a bit of truth to this statement when you consider how much of networking professionals’ time, energy, and budget has traditionally been spent managing complex network routing decisions. These decisions were key to stitching together different corporate sites and branches to the data center, while at the same time having to work with multiple internet service providers to ensure fast, reliable access for their users and a responsive application experience. Where this has gotten tricky over the last few years is aligning these network objectives with the growing security requirements facing enterprises. The problem has only worsened with the migration of applications and data to the cloud and SaaS, increasingly complex attacks, combined with the more recent explosion in remote work.

What is hairpinning?

Most enterprises today leverage an architecture that relies heavily on “hairpinning” or what’s also commonly referred to as traffic backhauling. In a networking context, hairpinning refers to the way a packet travels to an interface, goes out towards the internet but instead of continuing on, makes a “hairpin turn”—just think of the everyday instrument used to hold a person’s hair in place—and comes back in on the same interface. The classic scenario is the branch office, where no traffic should enter or exit without first getting security checked. Deploying a standalone security stack at every branch, across dozens or even hundreds of branch locations around the world, could be a viable strategy but from a cost, complexity, and administrative burden perspective it would be a nightmare.

Instead, the preferred approach has been to have all client requests to the internet sent (or hairpinned) from the branch back to a central location, like the data center, where security enforcement happens, and only then—after being scanned—the traffic goes onward to the internet. The same applies whether it’s making a request for web content or interacting with a business-critical SaaS app. On the server response, the traffic then needs to follow the same circuitous path back through the data center, to the branch, and ultimately to the user’s desktop. One doesn’t need to be a network engineer to realize this approach is going to impact user experience, adding latency and slowing things down significantly. Putting user experience and ultimately business productivity aside, this approach also puts a greater burden on the expensive and hard-to-maintain private WAN links, like MPLS connections, that enterprises have relied on for a long time for bridging together their distributed enterprise.

The evolution of hairpinning to WAN/SD-WAN

With the unarguable shift of applications and data to the cloud, and the growing volume and criticality of this traffic, one of the great attractions of the cloud security model is to eliminate hairpinning and dramatically simplify network design. It’s also one of the key drivers for the booming SD-WAN market and the impetus for large-scale network transformation projects. This was covered in another recent blog titled “How Netskope NewEdge Takes SD-WAN to the Next Level.” The conclusion one can draw is that networking professionals would prefer to avoid hairpinning and the future will increasingly be about sending their traffic direct-to-net with a cloud-first approach to security. So why then would a customer select a cloud security solution that relies on a hairpinning network architecture?

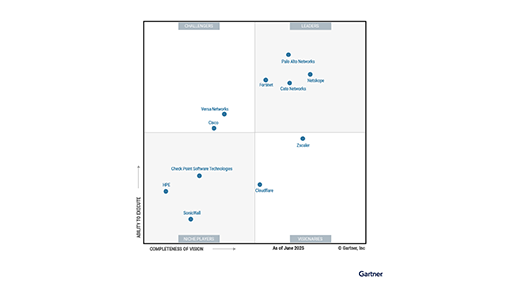

Unfortunately, one of the things that we’ve seen repeatedly in the market, and is commonplace with almost every cloud security vendor, is that they’ve architected their clouds all wrong. Essentially, what you find is they are repeating the mistakes inherent to traditional enterprise WAN design and replicating them inside a cloud form factor. The classic example of this is the virtual point of presence (or vPOP), an approach publicly known to be used by vendors including Broadcom/Symantec, Palo Alto, Forcepoint, McAfee, and others. (Don’t trust me, just check their websites and look for phrases like “Physical Location of Security Compute” or the term “vPOP”.) Not only do vPOPs provide a misleading view of coverage, but they also mislead on where traffic processing occurs within the cloud security vendor’s network.

At the most simplistic level, vPOPs provide an entry and exit point for traffic. One example discussed in a previous blog titled “Understanding Coverage Isn’t Just About Counting Data Centers” showcased a scenario with a remote user in Kenya. This user would need to connect to a vPOP in Johannesburg, South Africa, have their traffic sent to Frankfurt, Germany for processing, and then back to Johannesburg before the user’s request would head out to the internet and the web, cloud, or SaaS app they are trying to access. Just imagine the latency introduced with this back and forth of traffic, routing across huge distances, over multiple networks, ultimately slowing the user experience to a crawl. The conundrum is that vPOPs are literally traffic hairpinning all over again with the same implications on complexity, latency, and potentially cost.

And when vendors depend on public cloud infrastructure such as AWS, Azure, or GCP, they are either relying on the public cloud provider’s edge data centers to provide regional exit points for the traffic (Palo Alto). Or even worse, and far more commonly, they backhaul over the congested and unpredictable public Internet and use a “phone bank” of egress IPs, each registered in a different country, to implement their vPOPs (everyone else). The same problem manifests itself all over again, with traffic having to be steered over huge distances, backhauled and hairpinned between multiple locations, before eventually getting to the few—often less than 30—unique locations in the world where compute resources are located and security traffic processing can take place. Customers think they are buying into a cloud strategy for going direct-to-net with the critical security protections they require, but what they are getting is the same old network problems of the past re-implemented inside the cloud. This is the dirty secret of most cloud security vendors.

The power of NewEdge

Another nightmare example of hairpinning within a well-known cloud security vendor’s network came up recently with a customer we were working with in Latin America (LATAM). While the vendor advertises four LATAM data centers, they really have three vPOPs and a public cloud region in LATAM—namely vPOPs in Chile, Argentina, and Colombia, and VMs running in GCP Brazil. While users in Brazil were served from GCP Brazil, all other countries in LATAM were served from the US. LATAM traffic had to get backhauled to the US for processing and security policy enforcement. Not only did this vendor’s approach mislead tremendously on coverage—it seems they have only one LATAM data center and not four!—but this hairpinning-dependent approach introduced hundreds of milliseconds of latency. Even worse the customer saw decreased overall throughput due to this high latency (because throughput is inversely proportional to latency with TCP), increased error rates and packet loss, and overall lower reliability. Until talking with Netskope and learning about how we’ve designed NewEdge, this customer was on the fence about embracing cloud security and was close to doubling down on their existing physical appliances and ugly MPLS WAN architecture.

Many vendors claim vPOPs are the only way to deliver a seamless user experience, so for example, users get their Google search results or ads localized appropriately for their specific location or region. The reality is that any vendor relying on the public cloud instead of their own data centers to deliver a cloud security service is limited to the cities and regions that their cloud vendor offer compute (VM) services in, so they have no choice but to backhaul and use vPOPs to try to reduce the chances that the backhauling doesn’t result in content localization, geo-blocking, or other issues resulting from being routed to a far-away region.

We’ve hammered on this point in other blog posts, but the approach Netskope has taken with NewEdge is truly different and that’s why we’ve invested more than $100 million to build the world’s largest, highest-performing security private cloud. NewEdge embraces a direct-to-net model to streamline the traffic path and focus on network simplification while achieving superior reliability and resilience. We don’t rely on vPOPs or the public cloud, so our performance is better and more predictable. And every one of our data centers is full compute, with all Netskope Security Cloud Services available. All of this ensures the fastest, lowest latency access for users, whether their on-ramping from a café in Milan, a branch office in Hong Kong, or the company’s headquarters in New York City. Plus, the highly-connected nature of NewEdge, with extensive peering with the web, cloud, and SaaS providers that customers care most about truly gives NewEdge, and Netskope customers, an advantage. It’s time for customers to get informed about the dirty little secret of most cloud security vendors’ networks and ensure their selection of cloud security services doesn’t repeat the mistakes of the past, like with hairpinning.

To learn more about Netskope and NewEdge, please visit: https://www.netskope.com/netskope-one/newedge

Back

Back

ブログを読む

ブログを読む