Summary

Netskope Threat Labs has discovered a campaign using fake installers to deliver the Sainbox RAT and Hidden rootkit. During our threat hunting activities, we encountered multiple installers disguised as legitimate software, including WPS Office, Sogou, and DeepSeek. These installers were mainly MSI files that were delivered via phishing websites. Both the phishing pages and installers were in Chinese, indicating that the targets are Chinese speakers. We can attribute this attack to Silver Fox (a China-based adversary group) with medium confidence based on the TTPs, particularly the phishing websites, the fake installers for popular Chinese software, the use of Gh0stRAT variants, and the targeting of Chinese speakers,

In this blog post, we’ll explore how the MSI payload is delivered, loaded, and executed in the victim’s machine.

Key findings

- Netskope Threat Labs has discovered a new campaign using fake installers for popular software, including Sogou and DeepSeek, to target Chinese speakers with malware.

- The malware payloads include the Sainbox RAT, a variant of Gh0stRAT, and a variant of the open-source Hidden rootkit.

- Based on the nature of the campaign, the payloads involved, and the users being targeted, we can attribute these activities with medium confidence to the Silver Fox group.

Details

The infection starts when the victim accesses a phishing website and downloads a fake installer from it. The example below illustrates a website that mimics the official WPS Office software website.

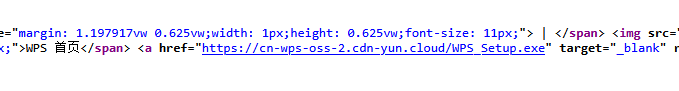

By inspecting the page source, we can see that when the victim clicks on the download button, a file is downloaded from a different URL.

During our investigation, we discovered fake installers for multiple software applications, including Sogou, WPS Office, and DeepSeek, presented on different counterfeit pages. Most of the fake installers we found were MSI files, except the WPS Office one, which was a PE installer. In this blog post, we’ll focus on the analysis of the MSI files.

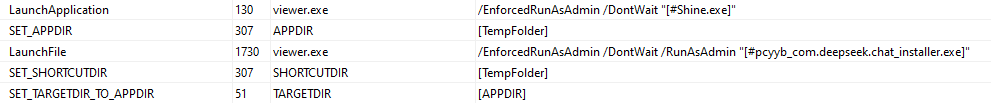

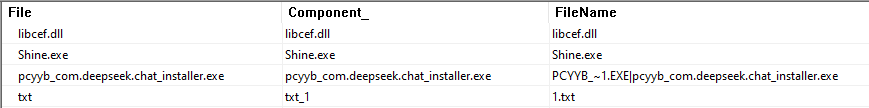

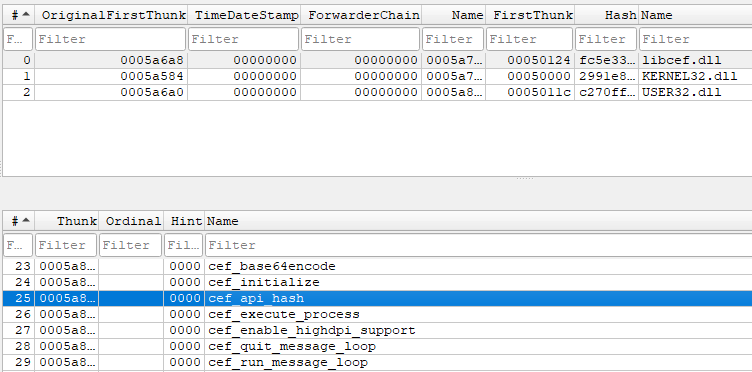

All the MSI files analyzed contained pretty much the same behavior, which consisted of the execution of a legitimate file named “Shine.exe”, used to side-load a malicious DLL “libcef.dll”, and the execution of the genuine installer software.

The malicious DLL is a fake version of the real libcef library, which is part of the Chromium Embedded Framework (CEF).

Among the mentioned files, the MSI installer also drops a file named 1.txt in the same directory. This file contains shellcode and a malware payload, which are loaded and executed later.

When executed, the MSI file presents itself as a regular installer and installs the actual software. In the meantime, the Shine.exe file is executed and side-loads the malicious DLL.

The malicious DLL code starts in an exported function named “cef_api_hash,” which is called by the Shine.exe file itself during execution.

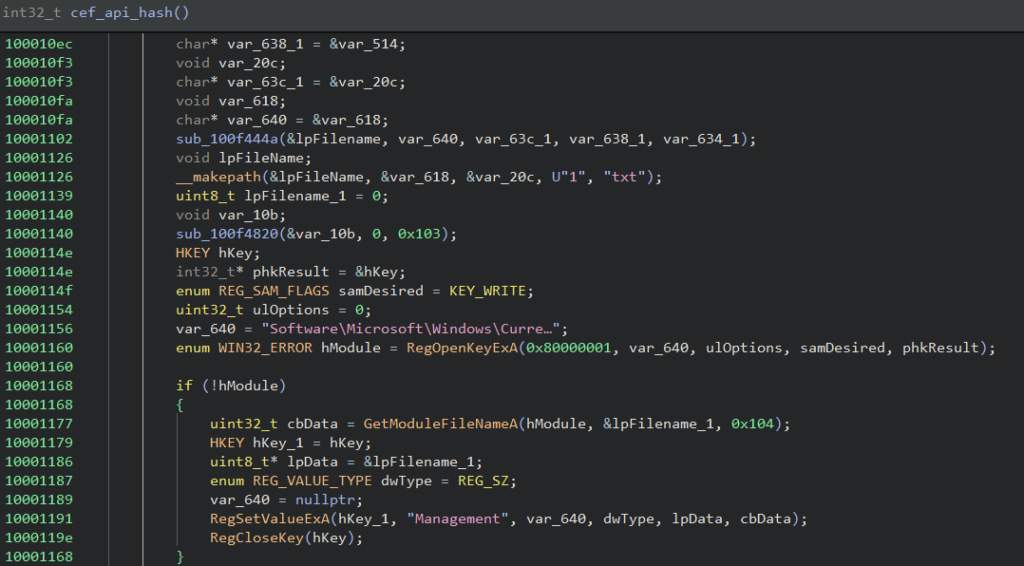

The called function performs three major tasks. First, it sets the path of the main binary being executed (Shine.exe in our case ) to the Windows registry Run key with the name “Management” to maintain persistence in the system.

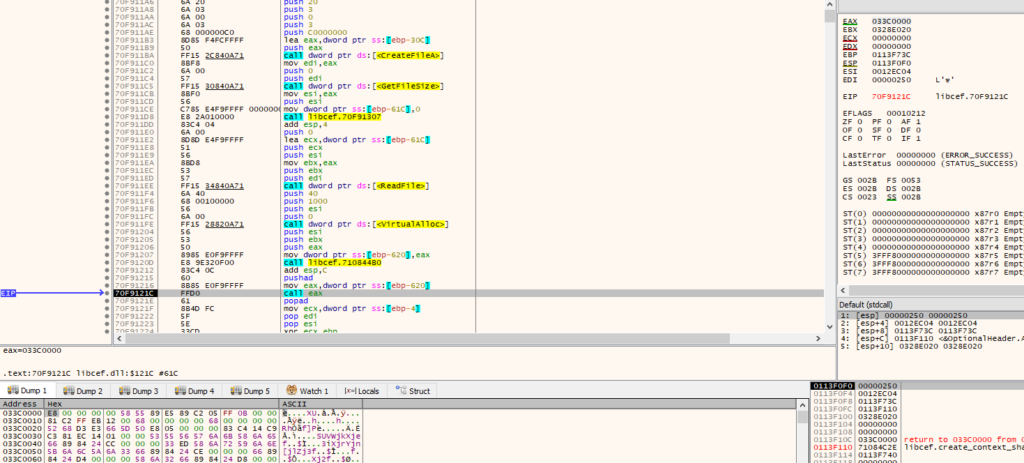

After that, it reads the content of the “1.txt” file into a buffer, allocates memory, and writes the read content to it. The final step is to redirect the control flow to the first byte of the read file, which is the start of a shellcode payload.

In all the analyzed files, the shellcode has 0xc04 bytes in size. The code used in the shellcode is based on the open-source sRDI tool. The idea behind the tool is to load a DLL into memory reflectively, call its DllMain function, and then invoke an exported function, which is where the malicious payload’s actions begin.

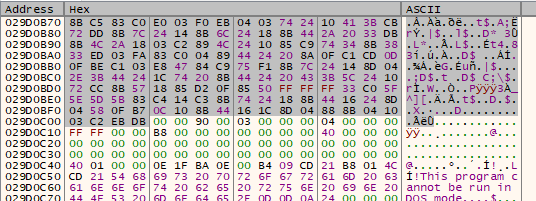

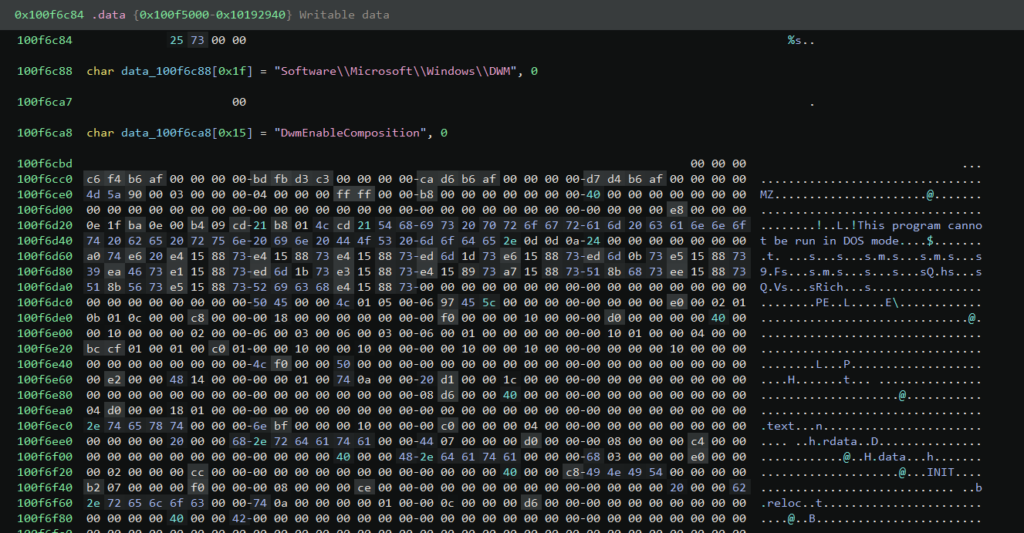

The loaded DLL is present at offset 0xc04 in the 1.txt file, and its DOS signature (“MZ” bytes) has been removed as an attempt to bypass forensic tools.

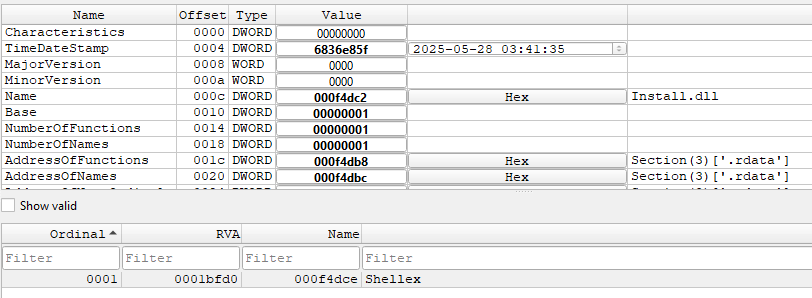

In the analyzed samples, the DLL name is “Install.dll” and the exported function executed is “Shellex”.

During the analysis, we identified the DLL payload as being the Sainbox RAT, a variant of the open-source Gh0stRAT.

The .data section of the analyzed payload contains another PE binary that may be executed, depending on the malware’s configuration. The embedded file is a rootkit driver based on the open-source project Hidden.

The RAT creates a service named “Sainbox” for the rootkit and loads it using the NtLoadDriver function. The primary goal of the rootkit is to conceal items such as processes, files, and registry keys and values. It does so by using a mini-filter as well as kernel callbacks. It can also protect itself and specific processes, and contains a user interface that is accessed using IOCTL.

The Sainbox RAT provides the attacker full control of the victim’s machine, allowing them to download and execute other payloads, steal sensitive data, and more. The Hidden rootkit provides some stealth, hiding the payloads, protecting processes from termination, and otherwise trying to prevent security and monitoring software from detecting the RAT and its activities.

Conclusions

This blog post is yet another example of attackers leveraging the popularity of AI for malicious purposes. Here, the phishing sites act as bait, and the payloads are hidden alongside the legitimate installers, a technique designed to avoid raising suspicion. Using variants of commodity RATs, such as Gh0stRAT, and open-source kernel rootkits, such as Hidden, gives the attackers control and stealth without requiring a lot of custom development. Netskope Threat Labs will continue to monitor the evolution of the Sainbox RAT and the TTPs of the Silver Fox group.

Attribution

Attributing activity to a specific adversary group is challenging. Adversaries attempt to conceal their true identities or intentionally launch false-flag operations, in which they aim to make their attacks appear as though they originated from another group. Multiple groups often employ the same tactics and techniques, with some even using the same exact tooling or sharing infrastructure. Even defining adversary groups can be challenging, as groups evolve or members move between groups. For these reasons, adversary attributions are an ongoing process that evolves as new information becomes available and the landscape changes.

Netskope uses three levels of attribution:

- High Confidence: The attribution is supported by strong corroborating evidence from multiple sources. Although this is the highest level of confidence, there is still a chance that the attribution is incorrect.

- Medium Confidence: There are several pieces of evidence linking to a specific adversary, but there may still be some ambiguity. These attributions rely on consistent TTPs, infrastructure, tooling, and context.

- Low Confidence: Some evidence indicates a particular adversary, but there are significant information gaps, or the evidence could be easily forged.

IOCs

All the IOCs and scripts related to this malware can be found in our GitHub repository.

Back

Back

Read the blog

Read the blog