Introduction

In our recent blog, Who Do You Trust? OAuth Client Application Trends, we took a look at which OAuth applications were being trusted in a large dataset of anonymized Netskope customers, as well as raised some ideas of how to evaluate the risk involved based on the scopes requested and the number of users involved.

One of the looming questions that underlies assessing your application risk is: How does one identify applications? How do you know which application is which? Who is the owner/developer? as well as a host of other related questions such as which platform, version, or what is the release history and bugs associated with the application.

This is particularly problematic in the context of the trust these applications are granted in accessing user data or other resources in your organization.

This blog post delves deeper into the problems and outlines some approaches on how to deal with a lack of information and processes for application identity.

OAuth application trust

Let’s quickly review the OAuth application trust/approval process to explore what we know about the applications we’re trusting. Although we will look at Google OAuth applications, much of this applies to other OAuth providers as well.

An application (which could be a website/web app, native/mobile application, or device), when it needs to access a user’s data or resources, will redirect the user to an authorization service (e.g. Google Identity) to authenticate and authorize the access. Here’s a flow when logging into Google’s own gcloud CLI tool, which needs to access a user’s Google Cloud environment:

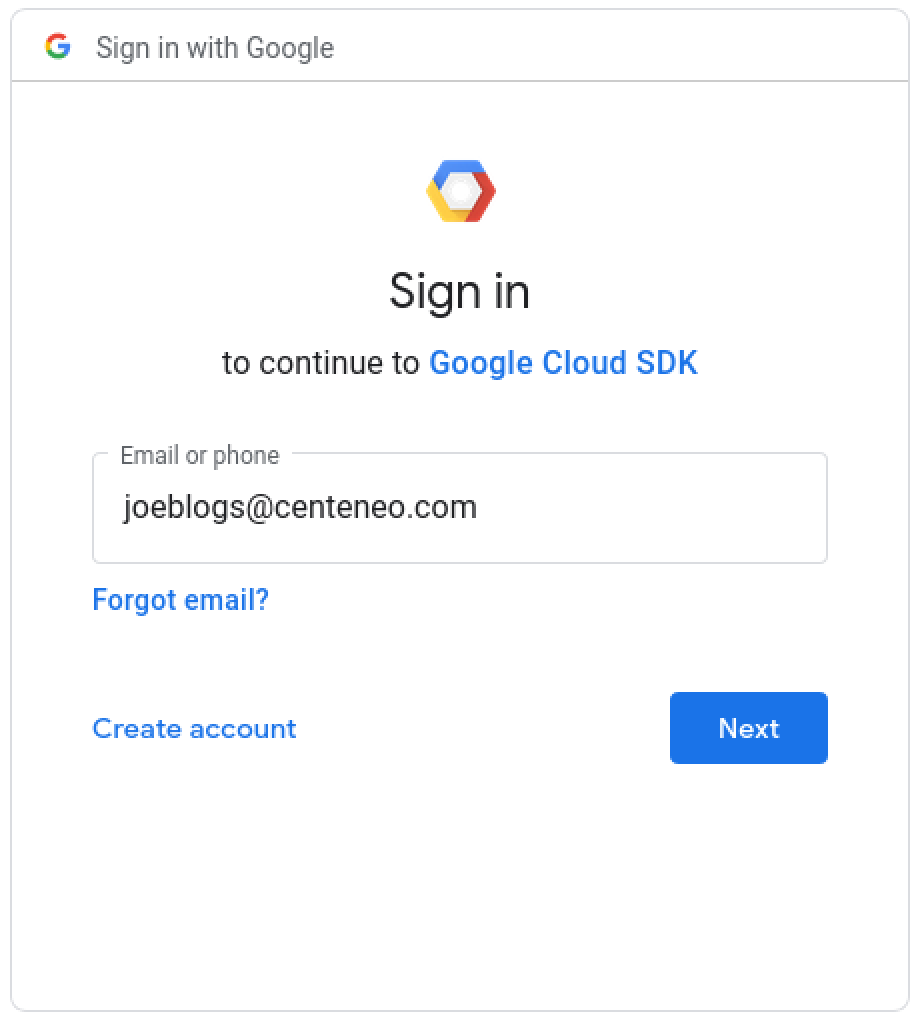

1. Application requests authorization by redirecting the user to the identity/authorization provide

$ gcloud auth login [email protected] --force

Your browser has been opened to visit:

https://accounts.google.com/o/oauth2/auth?response_type=code&client_id=32555940559.apps.googleusercontent.com&redirect_uri=http%3A%2F%2Flocalhost%3A8085%2F&scope=openid+https%3A%2F%2Fwww.googleapis.com%2Fauth%2Fuserinfo.email+ht...

2. User authentication: Enters username

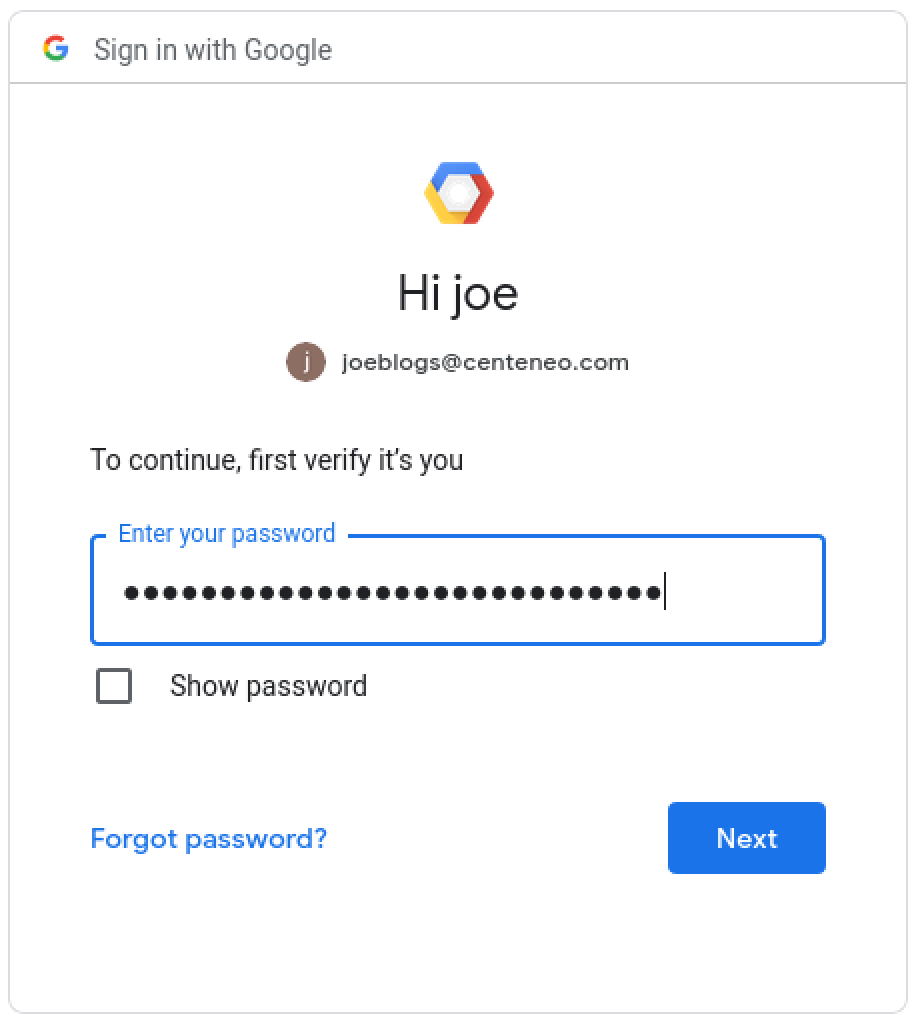

3. User authentication: Enters password

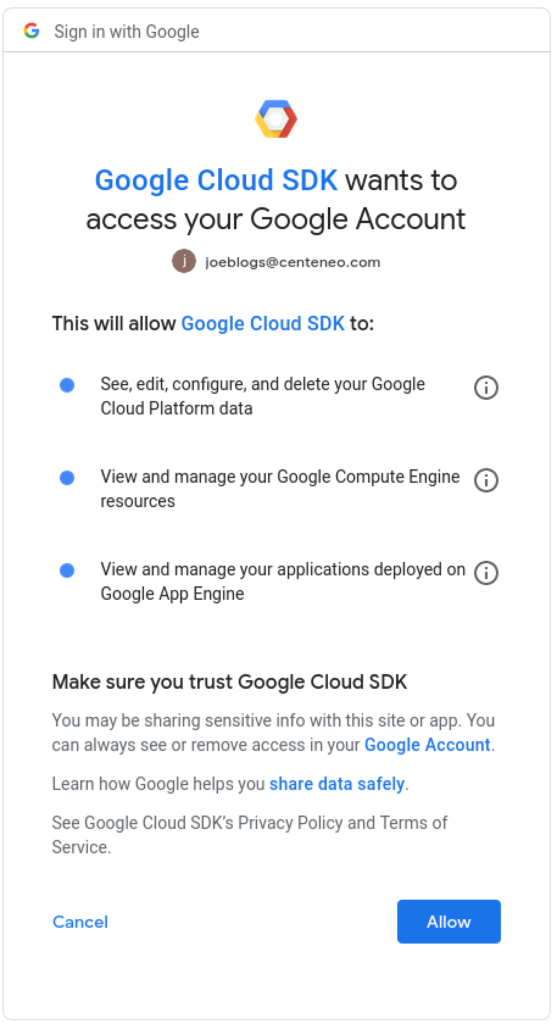

4. User authorization: The user is presented with a consent screen and approves the scopes requested by the application.

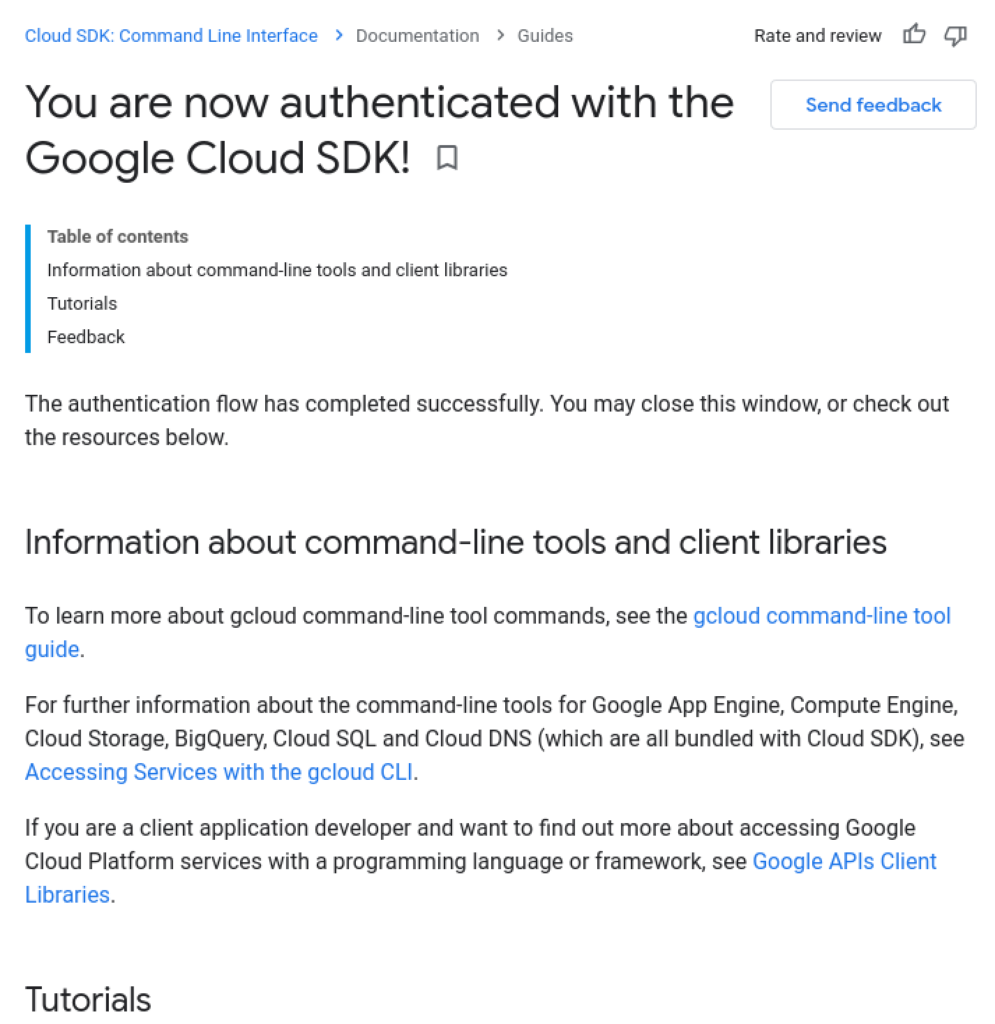

5. Confirmation message: In some cases, a successful authorization message is shown.

6. Application continues: The application has retrieved the user’s OAuth access token and can now access resources.

$ gcloud auth login [email protected] --force

Your browser has been opened to visit:

https://accounts.google.com/o/oauth2/auth?response_type=code&client_id=32555940559.apps.googleusercontent.com&redirect_uri=http%3A%2F%2Flocalhost%3A8085%2F&scope=openid+https%3A%2F%2Fwww.googleapis.com%2Fauth%2Fuserinfo.email+ht...

You are now logged in as [[email protected]].

$ gcloud projects list

From a user perspective, the application identity is given by the application name, Google Cloud SDK, which is seen in step #2 (initial login) along with a logo and steps #4 and #5 (authorization and confirmation). When the user is initiating a login process with an application they installed locally like gcloud CLI, this may not raise any concerns.

Application identity in the context of a phish

But if this were a phishing attack that starts with a fake application and steps #2 through #4, as we detail in the New Phishing Attacks Exploiting OAuth Authorization Flows series, then there are several concerns in terms of knowing whether to trust the application or not:

- The application name is arbitrary. In fact, it is set by the developer, and can be anything.

- Similarly, the logo could be nothing or any logo.

- Optionally, application developers can provide their domain, but it is not required

- The verbiage of what is trusting or accessing is confusing. Although tangential to application identity, it confuses everything for the user e.g.

- “Sign in to continue to Google Cloud SDK” in step #2 (wait, is that the name of the CLI?”

- “Google Cloud SDK wants to access your Google Account” in step #4 (my Google Account means my Google Cloud environment?)

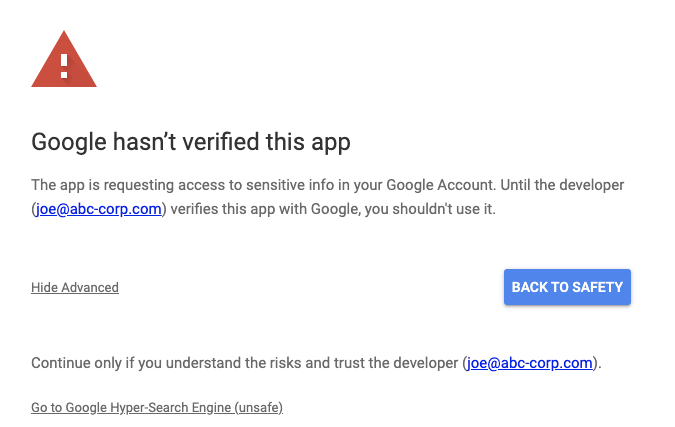

- There is a verification process by Google, but is required only if you request sensitive or restricted scopes (e.g. admin-level privileges). In this case, gcloud CLI is verified by Google, so nothing is flagged. With an unverified application, after authenticating in steps #2 and #3, you would see a warning like this:

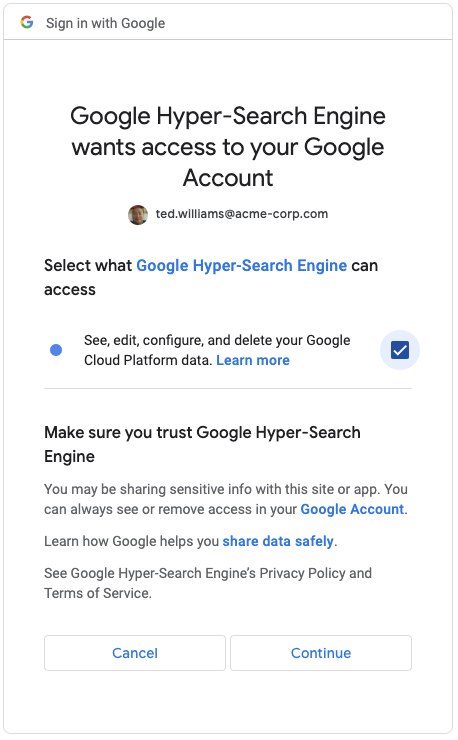

This is similar to the safe-browsing warning in Chrome. You can click the Advanced link as shown above in order to continue on, which brings you to the consent screen:

Where’s my application registry?

If we compare this against DNS and the need for understanding website identity in order to safely browse, DNS registrars have no equivalent in the OAuth application world. In theory, each OAuth provider could provide an application registry as they have a lot of information about each application’s developer but it is not exposed to the end-user, except for a few small pieces of information that are mostly controlled by the developer.

Verified, I guess

The good news is that there is a verification process that is not necessarily easy to bypass. There are in-depth security reviews and money required to make it through verification if you are requesting the most sensitive scopes.

The bad news is that verification, in general, is not a silver bullet because, in related security domains, it is either too complicated or ignored by end-users, for example:

- Installation of unverified apps on desktops or mobile

- Clicking through safe-browsing warnings

- Ignoring SSL cert warnings in browser

From a security perspective, we certainly aren’t relying on end-users to make use of any verification information to keep themselves secure—that’s where automated security controls come in. And from that perspective, having all of the verification information programmatically available with appropriate information to enforce blocking of OAuth application trust would be valuable.

The analogy is having programmatic access to passive DNS information and SSL certs in order to make determinations about blocking browsing to suspicious websites.

Additionally, this discussion is centered on the initial user flow and is focusing on blocking of user approval of suspect applications. For the security operations teams, having access to application identity including verification information would be crucial during incident response and investigations.

Your id is your name?

Returning to the topic of identity, one of the challenges is that the user is presented primarily with non-unique information set by the developer in order to identify themselves. A common technique used by attackers when phishing is to create a “fake” OAuth application with a name very close to something legitimate e.g. Google Hyper-Search Engine, or Google Workspace Drive. With all the rebranding of applications, it’s even more confusing to discern which application is which solely by the name. The same issues apply to logos if they are used.

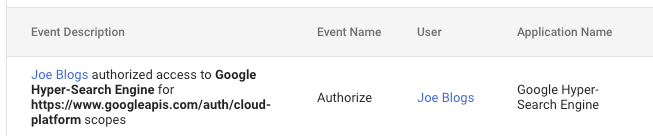

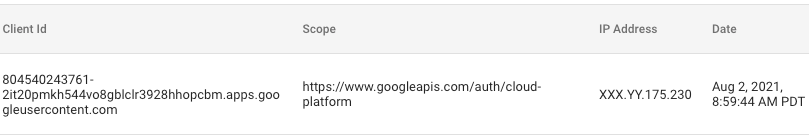

There is an application (client) id that is created when an application is registered by the developer. It is not seen by the user, but is logged in the audit logs and accessible by Google Workspace administrators:

The id, although unique, has little value because we don’t know if it refers to a valid application from a trusted organization.

Did you change your name identity?

In the world of websites, domains tend to be associated with trademarks and company identities and often are stable. Companies introduce sub-domains and alternative short domains that redirect, but there is a stability that helps with website identity. Along with the registrar information, which can point to administrative owners, organizations, and contact information, domains help you understand whether you’re dealing with a known or same entity.

With OAuth applications, much like mobile app stores, there aren’t conventions for keeping the same OAuth application name or id. Meaning, if a major new version is created, while the old version is still maintained, one may get a new OAuth application with the same or different name, with a different id. This only confuses the situation in terms of knowing what or whom you’re dealing with.

Tell me about your family…

What is also needed, is not just a flat list of applications tied to owners, organizations, or developers with unique ids, but relationships to capture the different versions or platform ports of the same applications. Much like families of malware, we need to categorize families of applications.

For example, we need to know Slack has 8 different versions: 4.x for iOS, 4.x for Android, 5.x for Mac, etc. The platform, version, and release date are just some of the metadata required to clearly identify applications in order to make judgments about security risk.

Where did you say you were from?

Ultimately, a key part of application identification is the entity behind the application, i.e. who developed it. This could be a company or an individual. We probably cannot do more than what is done in other application markets, but at least having an active website domain, name, contact information, and company name, would go a long way to helping identify and assess applications.

What is an “Untitled project” application?

Complicating all of this, are applications that are named “Untitled project”—sometimes because developers are testing, but also because applications can be created in different ways—and in Google Cloud, some of those are closely tied to creating other resources like projects. It’s complicated by the fact that there are multiple types of applications including desktop, web, device, and mobile, each of which may be developed slightly differently.

Application status

The status of an application is important to understanding the identity as well. Applications not only can be in development/testing but Google OAuth applications can also be set to Internal or External, which have implications on who can access/approve the applications (e.g. internal to the domain of the application developer or external users; or whether only a hard-coded list of test users can access the application).

Verified, in this case, could simply be one of six application statuses.

What’s “Deprecated API” mean?

The scopes requested by applications are logged e.g. openid or drive.read or cloud-platform. However, there is also a “Deprecated API” scope logged. The reason this is related to application identity is that the scopes being requested are often a useful attribute that one would want from an application registry without having to comb through audit logs.

And “Deprecated API” highlights the need for granularity and specificity in this information. It appears to be a catch-all term to cover just that: deprecated API usage, which occurs constantly. Knowing that an application is requesting scopes or permissions for older APIs (potentially less secure ones or non-recommended ones) is important to assess whether an application is being maintained properly, much like we assess mobile software by its recent release history.

Is the sky getting closer?

No, it’s not falling, but perhaps the cloud cover is a bit lower than we’d want. OAuth application attacks and security feels like the wild west. However, there are concrete measures you can take to compensate for sparse application identity and information:

1. Policy: Start by clearly determining which OAuth applications will be allowed in the organization–essentially form an approved/allowed application list, make it as short as possible, and then take steps to enforce it.

2. Prevention: Use the Google security controls available to lock down application trust actions or allowed applications. This will decrease the volume of application issues, which mitigates not having adequate identity information. Specifically, here are areas to review:

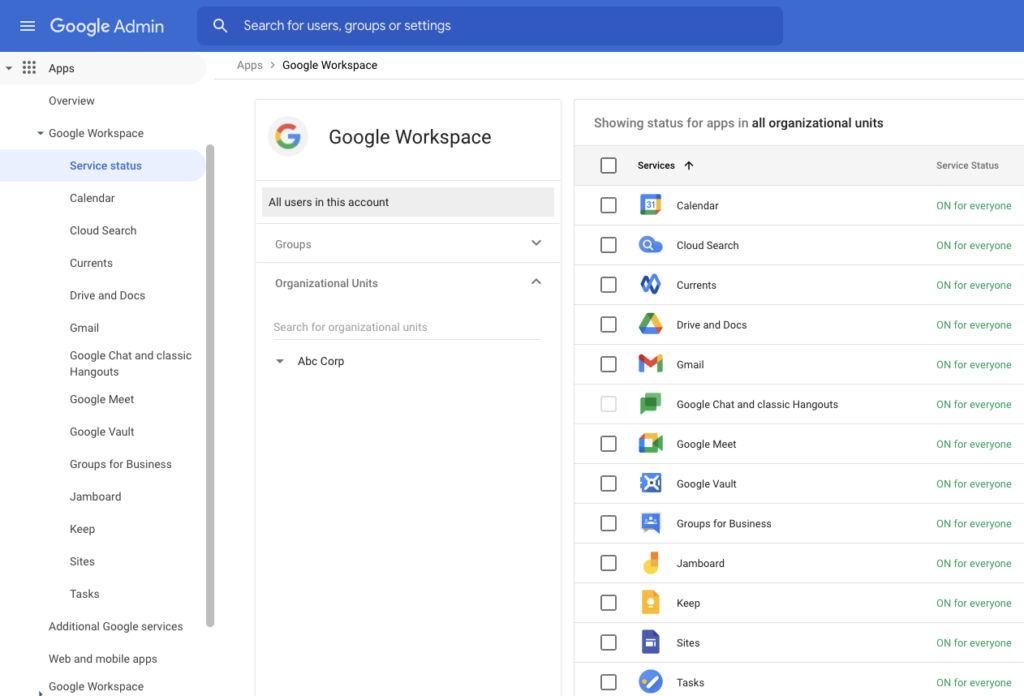

- Turn OFF unused Google Workspace applications in: Google Workspace Admin Console > Apps > Google Workspace > Service Status

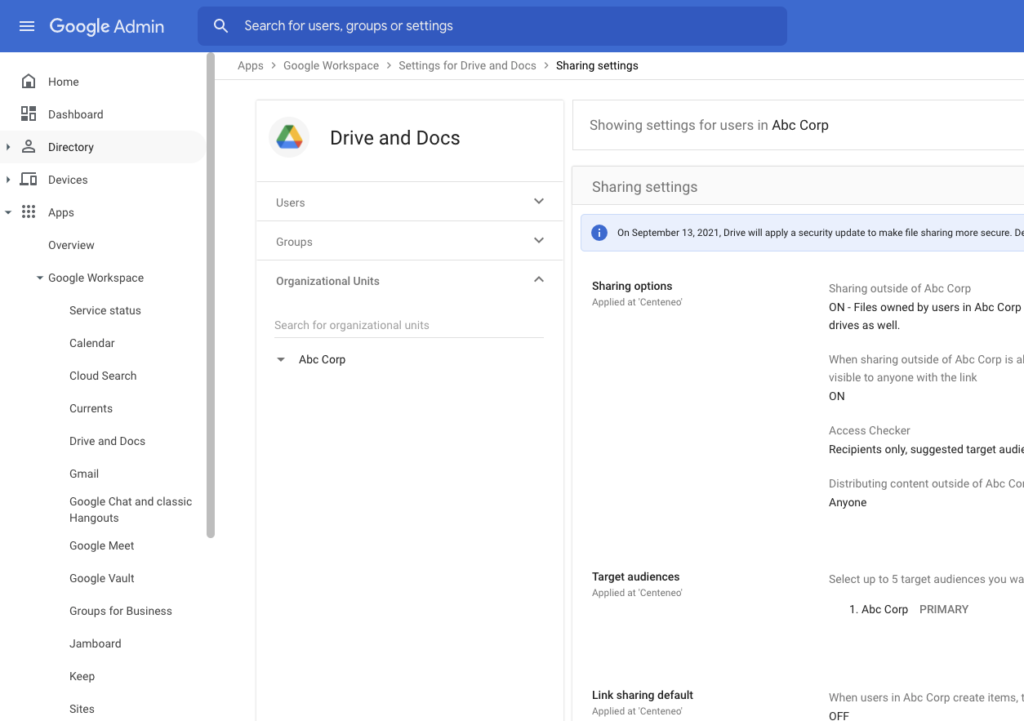

- Set appropriate settings (as securely as possible) for Google Workspace Apps in: Google Workspace Admin Console > Apps > Google Workspace > *

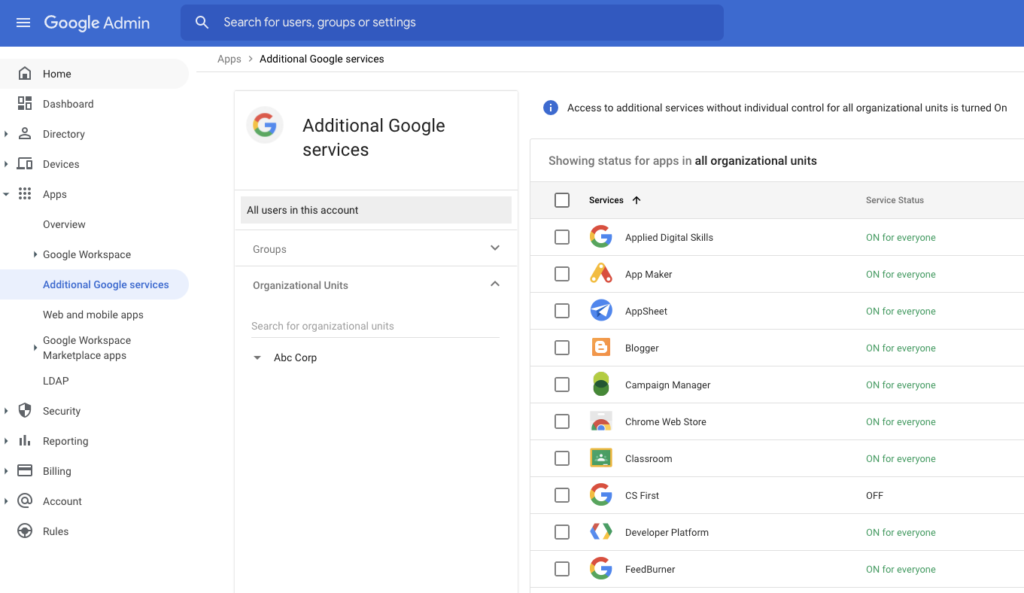

- Turn OFF unused Additional Google Services in: Google Workspace Admin Console > Apps > Additional Google services

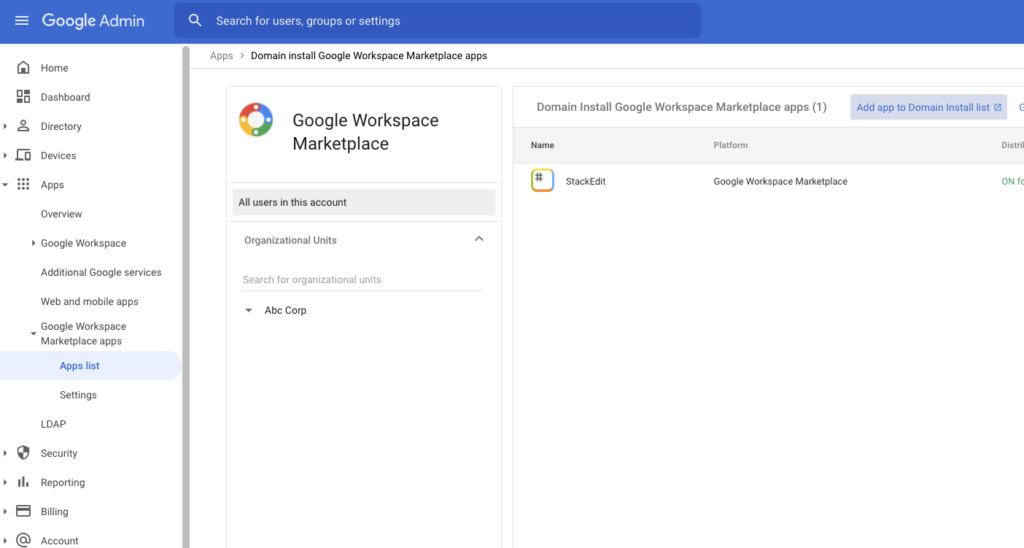

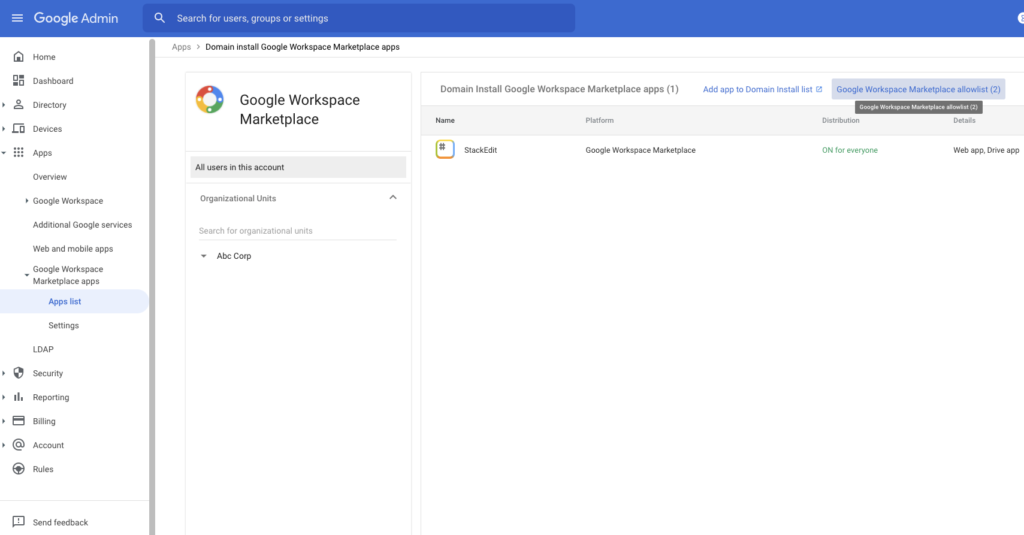

- For Marketplace Apps, domain install any corporate-wide applications in: Google Workspace Admin Console > Apps > Google Workspace Marketplace apps > Apps list > Add app to Domain Install list

- For Marketplace Apps, restrict user installs to an allow list in: Google Workspace Admin Console > Apps > Google Workspace Marketplace apps > Apps list > Google Workspace Marketplace allow list

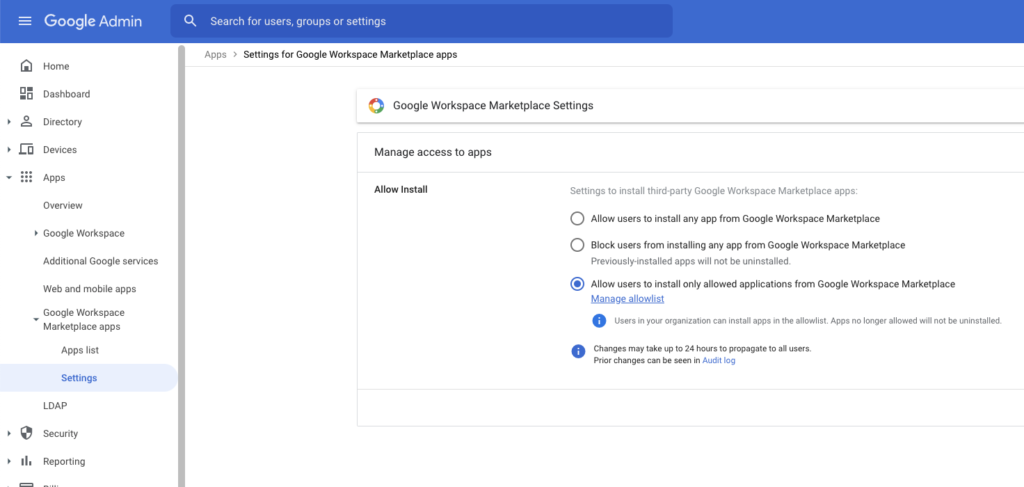

- Set up the user allow lists in: Google Workspace Admin Console > Apps > Google Workspace Marketplace apps > Settings

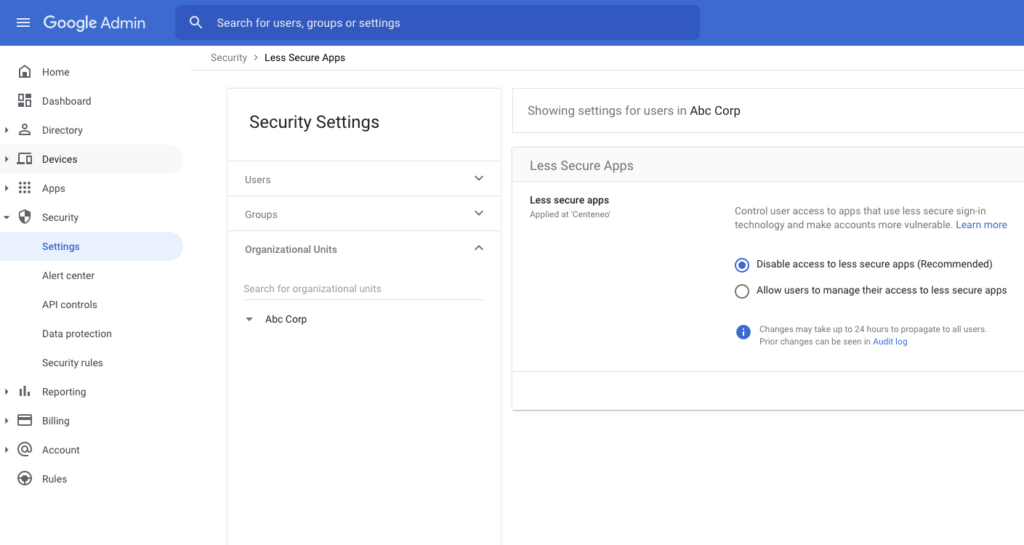

- Disable access to less secure apps in: Google Workspace Admin Console > Security > Settings > Less Secure Apps. Less secure apps are apps that don’t use modern security standards such as OAuth.

- Set up API controls to restrict access by applications

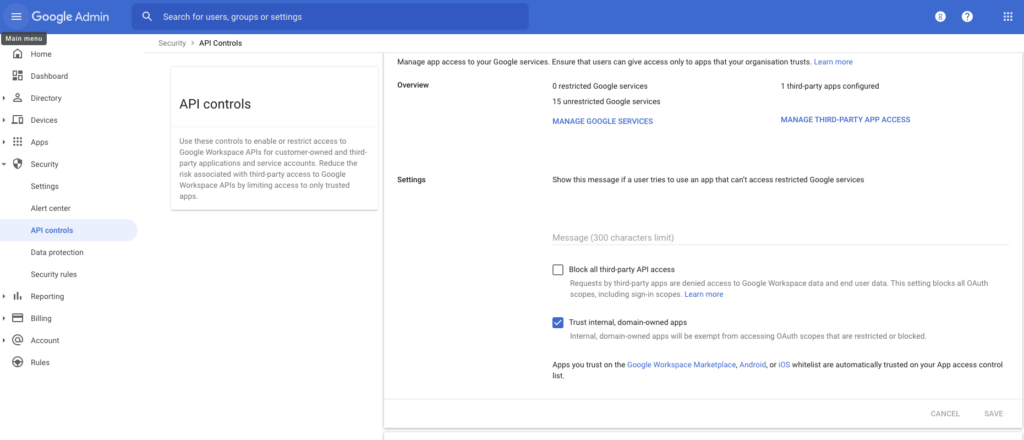

- Periodically review access granted to both Google Services and third-party apps in: Google Workspace Admin Console > Security > API controls > Overview > Manage Google Services | Manage Third-Party App Access

- If third-party apps are not used at all, block their access to any user data: Google Workspace Admin Console > Security > API controls > Settings > Block all third-party API access

- Determine whether to trust internal, domain-owned apps (are malicious insiders a threat?). To be most secure, do not trust internal apps. Set this in: Google Workspace Admin Console > Security > API controls > Settings > Trust internal, domain-owned apps

After locking down as much as you are able to, balancing security objectives with business needs, you can take additional steps of forming an application threat intelligence repository that can not only assist your lockdown efforts but also detection controls. These are discussed below.

3. Threat Intelligence: The above are first principles and help to minimize and mitigate risk from application trust issues. On the topic of application identity, treat it as you would treat important threat intelligence, and in the absence of standard feeds, start forming a useful repository based on your own usage. There are several fairly easy, steps an organization can take to help manage application risk:

- When creating or reviewing your allowed application list (step #1) collect basic application information including application client_id, OS, platform, version, release date, and company domain/URL. Track this in a spreadsheet, at a minimum, on a shared drive with access by security operations that will serve as a rudimentary application registry. A good time to do this is during the testing or trial stage of evaluating new applications.

- This information can then be used as the master allow list, which can be used to:

- Audit production application allow lists to ensure they have not changed unintentionally

- Create/check monitoring policies that will alert appropriate personnel if any application id not matching the allow list is found to be trusted

- This will also serve as reference information for investigation of OAuth application-related incidents.

- Consider moving the information from a shared CSV to a more structured datastore (e.g. a restricted RDBMS or a simple REST service on top). This will help automate steps (b) and (c) above.

4. Detection: Because there may be business or user limits on how far you can lock down the environment, detection controls are a good alternative to securing the environment by alerting administrators on potentially suspicious activity that should be reviewed and then possibly remediated. It’s similar to running an IPS in detect mode vs blocking mode. For real suspicious activity, you will allow more time because this is a reactive model, but you gain a more tenable approach that does not impact the business/users until you are confident that controls, like the application allow list, reduce risk more than decrease productivity.

So, instead of strict enforcement of an application allow list, consider allowing a more flexible policy of application trust and then alerting on those applications that do not match your “soft” application allow list. This allows you to review the list and user behavior and assess whether the allow list helps block risky apps without adversely affecting users or business productivity.

Conclusion

OAuth application identity is a challenge today because there is little information available to end-users or security personnel to assist with assessing the risk of newly trusted applications or with incident response involving OAuth applications.

Several factors contribute to this, including the lack of an application registry that is accessible programmatically and that maps a unique application identifier to important metadata, including:

- Name, version, platform, release date/history, and app URL

- Application status (verified, testing/prod, internal/external)

- Developer/owner, owner domain, and contact info

This increases OAuth application risk when determining which apps to trust or during investigations.

Despite these challenges, there are several steps that can be taken today to mitigate these issues:

- Create clear policies on approved/unapproved applications

- Prevent unauthorized applications from being trusted by utilizing Google Workspace Admin security controls to control approvals.

- Create your own application registry for approved applications and apply this to:

- Prevention controls

- Detection controls (alerting)

- Incident response application intelligence to aid in investigations of oauth-related activities

Back

Back

Read the blog

Read the blog